|

As my Shirley Graham Du Bois Creative in Residence tenure comes to a close, I am deeply inspired by my experience with Castle of Our Skins. My goals in applying included collaborating with musicians and artists of genres different from dance. This was definitely achieved and I’m excited about the people that I’ve met and the relationships I’ve begun to cultivate. These relationships are bridging a gap in my creative journey between musicians and my dance practice of choreographing and facilitating. Working closely with the COOS creative team has further affirmed and motivated my ambitions to strengthen and fortify my creative organization, Modern Connections. The thought and detail that goes into the COOS programming is clear and effective. It allows budding and professional artists opportunities to engage with professional development and performance experiences that enhance their artistry. It’s important for Black perspectives to continue to be represented in the field of art and music, particularly in this city and made accessible to people in those communities. My life completely changed when I attended undergrad and experienced my first Black teacher (professor of dance). I had a visceral response to her. At the time, I didn’t understand what the feeling was or how her guidance and training would impact the direction of my career. Seeing a Black woman with locs at the front of the room for multiple classes a week over four years time, sharing her knowledge encouraged me to step into my own excellence. She opened the doors to the world of African and African derived movement and history and I began to take myself and my training more seriously. Now, as an adult and mid-career artist, I understand that the feeling I had was that of transformation and connection, some may even refer to it as an intitian. Both transformation and connection remain a central component of my experience of the Self. I use dance as a method of processing and understanding the interconnectedness of people, culture and spiritual praxis. I’m able to deepen that understanding when I’m in a creative relationship with others. As I’ve mentioned in my first blog post, I believe that movement is the first form of communication and that it begins in the womb. I’m constantly noticing the movement of others and the way that movement informs our worldviews. Sometimes, I’ll sit somewhere in a public place and watch what’s happening; the stop lights changing, the trees swaying, the formation of the birds as they take flight, the gait of people walking, the placement of architecture, the smell in the air etc. It’s fascinating to see the ways in which we navigate together in an improvisational structure yielding life force energy and how that shifts through the seasons and with time. I remember a day while I was in Salvador, Bahia, Brazil waiting at the bus stop just outside of Pelourinho and the dance of the neighborhood as I looked on. It became a performance in my mind. Some people were moving quickly darting around those in their path while others were strolling leisurely, taking in the sights and enjoying the company of those around them. There were folks who were navigating in an altered state of consciousness but yet so clear in their own world. There were young people, older people, tourists and locals all intersecting and creating pathways through space. There were old buildings and new stores amplifying the sounds of the bustling neighborhood, protest chants and street vendors trying to make a sale. The ocean created an enchanting backdrop with the sun reflecting off the waters offering a majestic light as it moved toward the sunset. All of this happened at a moment in time that will never be experienced again, just as dance happens in a timeframe that can never be experienced the same way a second time. A true reflection of life. In my work I try to create meaningful dances with this in mind. What is it that I want to say about this moment? What am I sharing? How am I creating space for others to experience my curiosity in a way that allows their interpretations to interact with my idea. What am I archiving? As interconnected, intersectional people it’s imperative that our education and creative engagement with others includes spaces for ‘yes, and’ otherwise we risk perpetuating systems of oppression, erasure and harm. Erykah Badu said in an interview that “evolving involves elimination” and I believe that we need to eliminate the idea that the compartmentalization of expression is a comfortable, acceptable and/or necessary form of creating art. Black art and its expression is bold, ancestral, life affirming and engaging. COOS is embodying these truths in Boston. I hope to continue to add, evolve, eliminate, incorporate, integrate and share that in my own organization and creative work. Modern Connections is a multi-pronged dance organization that provides experiences to help people process information and ideas through workshops and performances. The Shirley Graham Du Bois Creative in Residence has helped me to grow upward as an artist as well as deeper into my Self. I am clearer now than when I began and grateful to have played, collaborated and developed more work and things to reflect on that will help me as I continue forward in my career and life’s purpose. I want to take time to share a note of thanks specifically to Ashe Gordon and Ciyadh Wells for their constant support and guidance during my tenure as Creative in Residence. Thank you for leading with compassion, empathy and flexibility. Your example has confirmed that thoughtful leadership yields outcomes that support organizational growth and community enrichment. Your work ethic and excellence is unwavering no matter the setting; a classroom, speaking at an esteemed event, performing on stage or producing an intricate, multi layered event. This resonates with me. To the next Creative in Residence, Carmin Wong, I hope that this opportunity offers you space to grow and breathe, to take risks and manifest a vision that speaks to your purpose as an artist.

0 Comments

Hello Again! Welcome back to my blogspot. In my previous entry, I shared about my motivation for applying to this residency, my background as an embodied practitioner, and laid the groundwork for what has been a journey of exploration and discovery. If you haven’t had a chance to read it yet, I encourage you to do so. In this entry, I'm excited to pick up where I left off and introduce you to my capstone project, 'Belonging.' This project has been a culmination of years of reflection, collaboration, and creative visioning. I look forward to sharing more about its evolution and impact. But before we dive in, I invite you to reflect on the significance of belonging in your own life. How have you experienced it? What ways do you identify or connect to your sense of belonging? Has it shifted over time? Feel free to share your thoughts and reflections in the comments below—I'm eager to hear your insights and perspectives. In a city that contends with creative brain drain, I am deeply committed to fostering greater inclusivity in artistic expression. I'm passionate about designing opportunities for individuals, regardless of whether they consider themselves artists, by providing spaces for them to develop their practice. This includes access to creative tools that can inspire new ideas and foster meaningful connections. Right from the beginning of my time as Creative in Residence, COOS has offered me an opportunity to do this. My capstone project, 'Belonging,' exemplifies how my art reflects my vision of 'being.' As a designer by nature, I've organized play since childhood, exploring interactions and creating scenarios with my imagination. This includes drawing, writing in code, and nurturing my curiosity about the world around me. When presented with the opportunity to develop and be part of the curation process of a work, I was excited. The idea of bringing my imagination to life was both thrilling and overwhelming. I vividly recall thinking, 'A capstone project at the beginning of my residency?! How will I manage?' It took considerable time to grasp the concept, but through numerous conversations and planning sessions, I realized that my years of creative play laid the groundwork for the culminating vision of 'Belonging.' Despite the current perception of the word and concept as cliché, ‘Belonging’ holds deep personal significance for me. This work began in 2020 during the quarantine. I had lost a lot of family members and loved ones, my routine and sense of self had been disrupted, and I no longer felt grounded in place. Originally from New Bedford, MA I found myself unable to go home to be with my family. Paired with my intense focus, I remained deep in thought about many things including the (brief) gift of time on this planet. Through the many disruptions around me, I began to ask the questions, what does it mean to belong to a person, to a place, to yourself? Little did I know, these questions would be the seeds of future creative explorations and offerings. As a choreographer, I work with a group of dancers in Boston. At the time of lockdown I had given up any ideas of making work or dancing in the ways that we had been doing for the previous 4 years. Up to the time of the shut down, I had spent almost every week of my adult life interacting with hundreds of people through dance classes and rehearsals. When everything closed, I was shaken to my core. Suddenly, I had no stimulation at all, it was jarring for me and those that I love not having access to one another physically. After a few months of dancing in my bright green kitchen over IG Live (#KitchenClasses), I needed to get back into the studio so I began trying to find ways to get together with my dancers and dig into the questions that I had been wrestling with. I had created a dance film commissioned by Emerson College’s Intercultural Affairs Department, took part in Urban Bush Women’s Virtual Generative Dancer Choreographic & Performance Lab, participated in a variety of panel conversations about place and identity, and co-created Moving Through The Budget a residency that combined fiscal education, dance, facilitating group discussions. All of these endeavors helped me to process and eventually articulate the amalgamation of my experience. The beautiful thing about art is that the impact of a particular piece is different for each individual. After being invited as one of WBUR’s City Space’s “Ones to Watch: Boston’s Emerging Artists,” series in 2022, I began developing the concept of a workshop that offered the audience an opportunity to experience part of my creative process through reflective prompts, drawing, co-creating an altar space and connecting with people. This was designed to precede the performance component of the show. As the audience entered the rearranged lobby, the magic unfolded. Everyone present, shared in the vulnerability of exploring the questions I proposed around belonging and witnessed my personal vulnerabilities with loss and isolation. Following this performance, I was awarded a Live Arts Boston grant from the Boston Foundation to further develop this workshop structure. Over the course of a year, I delved deeper into the concept of belonging, gaining insights into the profound work people have been doing for decades to cultivate spaces that foster a sense of belonging. I was simultaneously blown away, inspired and amazed. It has since become an interest of discovery for me. Looking ahead to the opportunity to create a capstone project at the beginning of my time with COOS, I realized that this could be the perfect moment to synthesize my years of curiosity, play, and reflection From the press release written in October, ‘Belonging will include “Connection Stations” with participatory driven and artist curated workshops designed to deepen one’s connection to self. “Immersive experiences that make you question, reflect, and demand your attention are intriguing to me,” Artistic Director Ashleigh Gordon shared. “With Jenny’s guidance, I see Belonging, our 11th season opening performance, as being an experience that invites our whole selves to be fully present, to be engaged on a multi-sensory level, and experience what it feels like to be centered and included.”

How could I bring together local artists who have been working creatively with the theme of belonging and showcase a representation of what it means to belong to the Greater Boston area as an artist? My vision was to incorporate a multidisciplinary approach within the space. I was excited to include multimedia artist Crystal Bi, engineer and artist Nat Atnafu, wellness architect Jessi Rosinski, writer/poet Jacquinn Sinclair, Ga-Ewe folklore, performing artist, author and entrepreneur, Dzidzor (Jee-Jaw), guitarist Ciyadh Wells, marimbist, composer, Africana studies scholar, and cultural activist Steph Davis alongside my cast of dancers Erin Chiesa, Izzi King, Anelise Tatum, Imani Deal and Rachael Thomas to build this interactive performance art experience. The design of the space allowed attendees to choose their own adventure during the first hour, exploring each station’s offering and engaging expressively in response. The connection stations included zines, paper and pens, a phone booth that allowed you to hear a message and leave a message, a film of interviews with people talking about belonging, delicious comfort food from Zaz restaurant, ‘remote touch’ an interactive technology installation and an immersive exploration of self-belonging through breath, music, and reflection. The second hour featured seamlessly integrated dance, music, and spoken word performances, transporting the audience to another realm. In our fast-paced society where productivity is often prioritized, 'Belonging' offers a space for pause, reflection and acknowledgement that we are not solely defined by what we produce; rather, our existence is valuable enough. Over the years my exhibitions have received a variety of responses. Some people are moved to tears, overwhelmed by emotion, while others express surprise at experiencing art in such a visceral way. There's been a range which underscores that this work can serve as a portal to dig a little deeper into Self, to call a loved one, to reach out to a friend or neighbor, to sit in nature, etc. When considering what it means to belong to a person, I reflect on the importance of holding space and engaging in deep listening. A dear friend of mine often speaks about the intention behind the constellation of care, and over the past four years, I've come to realize that we are all interconnected, even in times of struggle. Reflecting on my sense of belonging to a place, I think of my experiences as a Black native woman from Massachusetts. It involves spending time in nature and grappling with the complex history of Boston, which serves as the epicenter of the successful yet problematic colonial, imperialist experiment of the United States of America. This reminds me of my responsibility to my surroundings and the ongoing need to examine my relationship with them. The city itself is a physical manifestation built upon the foundations of my kin and our culture. So, what does it truly mean to be connected to a place, to be of it rather than from it? Furthermore, what does it mean to belong to myself? Again I think of my dear friend who says, “You can only meet people at the depths that they’ve met themselves.” For me it’s about maintaining my practices, spending time with my loved ones, and nourishing my body and spirit while remaining in purposeful alignment with my life force energy. Amidst the myriad struggles and genocides happening globally, bearing witness to humanity’s suffering can be overwhelming. However my prayer and ongoing work are rooted in the belief that 'nobody is free until everybody's free,' echoing the sentiment famously expressed by Fannie Lou Hamer. Continuing from the press release, Oliver states, “As we continue to navigate multiple pandemics and the often-transient nature of Boston, I wanted to create the causes and conditions for folks to pause and reflect on their sense of belonging through transformative art making…” Hi! Thank you for stopping by to learn more about me as an artist and my time as the 2023-2024 SHIRLEY GRAHAM DU BOIS CREATIVE IN RESIDENCE. As a holistic artist working with the medium of dance, I combine contemporary Modern movement with aesthetics of the African Diaspora. This is the first of 3 blog posts that I’ll be sharing over the next 2 months and I’m looking forward to sharing about myself as an artist and the things that fuel my passion. Please feel free to engage with me in the comments if you have questions or notions that you’d like to share. What’s sparking joy for you or bringing you inspiration these days?

I’m honored that the review panel selected me for this opportunity particularly because my modality of artistic expression is one of embodiment. On the surface it might seem that my form is in stark contrast to musicianship but I view myself as a musician who uses my body as the instrument. It speaks multiple languages and has the ability to evoke emotions in myself and the viewer. Dance can be used for various types of healing including cognitive and neurological. Recent studies have shown this and we as African descendants have known this to be true for thousands of years. Thank you to those involved in the review process, it means a lot to me to have my approach recognized in this way. My motivation for applying to this residency stemmed from my desire to work across disciplines and to think about my creative process differently. Throughout my 18-year career as an artist, educator, and investigative learner, I have cultivated a trauma informed, culturally responsive, kinetic storytelling practice that expresses my experiences of the world and the sociopolitical realities of race, equality, inclusion, and hierarchy. For a lot of my life, I’ve compartmentalized myself as a way to connect with others and be accepted. This act has helped me succeed in some aspects while simultaneously creating confusion in and around me. The deeper that I journey into my practice the more I understand the necessity of connecting the various compartments of myself. In addition, I spent the majority of my childhood playing the clarinet and being surrounded by music. My grandfather and great uncle played the piano, my father played the drums in his younger years and my extended family had a fife and drum corps. In my studies, I’ve grown to understand the vital connection of movement, music and singing, and this residency seemed like a good way for me to continue to explore my discoveries. In the womb, movement is one of the first forms of communication that we engage with. As we proceed into adulthood, we often lose our intentional relationship to this vital form of expression and I’ve thought a lot about why this is. It is my belief that the oppressive systems in place benefit from us being separated from our bodies. This disconnect creates dis-ease in our nature-system and disrupts the natural flow. Being a lifelong embodied practitioner, I seek to reconnect bodies to this way of communicating. Movement can be a collaborative vessel for storytelling, re-imagining, cognitive development, proprioception, etc. and I'm inspired by artists both within and outside of my primary discipline. Spending the last eight years as a dance educator in academia has been transformative, but my own artistic enrichment has, at times, felt stagnant. I value cultivating community among purpose-aligned professionals and creating a network of mutual support and engagement. During my time with COOS, I've continued to work in this way, deepening my connection to the wider artist community here in Boston. My dance practice is informed by a mix of university and experiential learning including immersive dance intensives in Brazil and Haiti; formal concert dance training; and my spiritual proximity to African ritual spaces and ceremonies. I believe in the power of dance to catalyze meaningful and effective change in the lives of others, and I work at the intersection of dance, education, and collective collaboration to elevate systemic issues affecting Black and Indigenous people. In all elements of my work, I strive to create the causes and conditions for liberation, pause, and healing through movement. Although my background is in concert dance forms and I enjoy making work for the stage, after moving to Boston in 2005, I found myself increasingly reflecting on the limitations that concert dance performances have on a viewer. This prompted me to explore the transformative and liberating possibilities of dance beyond the proscenium stage. In 2014, I launched my first series of dance classes and shortly after, started my dance collective: Modern Connections. Through Modern Connections, I aim to push the edges of visceral movement and to inspire conversation, personal reflection, and community transformation. Over time, I’ve noticed the need to shift the idea of movement and dance from the margins of society into public visibility. To do this, I’ve cultivated partnerships with a variety of public, private, and government entities. For example, in 2021 and 2022, I worked with the City of Boston to create Moving Through the Budget: a collaborative storytelling, dance, and movement workshop that engaged residents around the City Budget and budgeting process. This project empowered over 100 residents in two neighborhoods with information, tools, and a pathway to amplify their voices about resource decisions that impact their everyday lives. Another core collaborator in recent years has been the Design Studio for Social Intervention (DS4SI). Through a variety of projects and events that aim to question the arrangements that we have as a society, DS4SI investigates how art can interfere with a condition or process to modify it or change its course. In 2022, I participated in DS4SI’s Civic Design course and was inspired to incorporate elements of their Ideas-Arrangements-Effects framework on social justice into my art making. In a city that contends with creative brain drain, I am dedicated to cultivating more access to art making. I’m devoted to designing opportunities for those who may or may not consider themselves to be artists by providing spaces for them to develop their practice and access high caliber creative tools that can inspire new ideas and ways of relating. Right from the beginning this residency has offered me an opportunity to do this. My capstone project Belonging is a great example of how my art making is reflective of my vision of ‘being.’ I’ll share more about this project and its impact in my next blog. If you made it this far, thank you! What is one thing that has inspired you after reading this? In what way does movement exist in your life? 2024 marks Julia Perry’s 100th birth year with today, March 25th being her actual birthdate. Already, there have been a host of celebrations in her honor. Last month in England, a weeklong celebration of Perry’s life and music took place at the Royal Northern College of Music. And just last week in New York City, COOS’ Artistic Director & Violist Ashleigh Gordon had the pleasure of witnessing several world premieres, engaging lectures, and even joined a stellar line up of musicians onstage to perform Julia Perry’s chamber work “Pastoral” for flute and string sextet. While Julia fell into obscurity in her later life before she passed in 1979, there has been a wealth of continued scholarship and advocacy focused on her music, her life, and her family. Eileen Southern, a scholar of Renaissance and Black American music, and the first African American woman tenured in the Faculty of Arts and Sciences at Harvard, wrote of her and countless other Black musical figures in her 1971 book: “The Music of Black Americans: A History.” Dr. Mildred Denby Green has a chapter on Perry in her 1983 text: “Black Women Composers: A Genesis”. Julia Perry’s most extensive biography and insight into her life and scores can be found in Helen Walker-Hill’s seminal book from 2007: “From Spirituals to Symphonies: African American women composers and their music.” There is also work happening today to diligently bring Julia Perry’s music to the forefront. Dr. Kendra Leonard, for instance, has created a free-to-use digital hub on Humanities Commons to assist with the exchange of manuscripts, published works, and scholarship on Perry. Julia's scores, many of which were thought to be orphaned manuscripts, and a number of them being illegible, are being engraved for publication due to efforts of a small but mighty team that includes:

So. You may be asking: "Who was Julia Perry and why are so many people interested in her?" Well, we're glad you asked! Julia Perry was born in Lexington, Kentucky on March 25, 1924, the fourth of five sisters, to an upper middle class and musically-enthusiastic Black family. At the age of 10, she moved to Akron, OH, where she studied voice (she was a mezzo-soprano), piano and violin, and was known as an “outgoing, cheerful, aggressive tomboy” by her childhood friend and cellist Kermit Moore. She received her training at Westminster Choir College in New Jersey, studying composition, voice, piano, violin, drama and conducting. She graduated with her bachelor’s degree in 1947; the same year Carl Fischer published her first work: a choral piece entitled Carillon High-Ho. She spent two summers in the Berkshires studying choral singing, conducting and composition at Tanglewood and many years living in Europe writing, performing, and studying with Nadia Boulanger and Luigi Dallapiccola among others. Julia was a conductor, and the only Black female conductor active during the mid-century years as noted by Eileen Southern, having "conducted a series of orchestral concerts in Europe under the auspices of the U.S. Information Service" in 1957. She was known to many as “Maestra” and prided herself on her “Toscanini precision” and “Stokowskian grace.” She wrote dramatic works including a three-act play, an epic poem entitled Graves of Untold Africans, and three (complete) operas including:

Beyond opera, she wrote about 100 works ranging from solo instrumental, sacred and secular songs, and chamber works with all sorts of creative instrumentation, to symphonies, works for band and concertos. About half of those works were lost due to lack of preservation or cataloging efforts. Of those that survived, only about a dozen or so are published. The rest are actively being sought after to engrave and bring back into concert rotation. A two-time Guggenheim Fellowship recipient, Julia’s health went south in her late 30’s. She suffered from Acromegaly, a hormonal disorder that causes the bones in one’s body to enlarge. In her 40’s, she suffered a series of strokes that left her paralyzed on her right side. Determined to continue to compose, Perry taught herself how to write with her left hand. By this point, her scores were so illegible that she needed to write the note names in her manuscript and often send messages of apology for their condition. Yet, for years, she determinedly sent her scores to colleagues, publishers, composers, and conductors for their consideration to program and record. She, who was celebrated and reached international success in her 30’s with her career-launching work Stabat Mater, was met with a slew of “no’s” in her 40’s and 50’s. She died from cardiac arrest in 1979 at the age of 55: a Black, disabled woman who had fallen into obscurity and severe economic hardships. So what makes her so interesting? Musicologist Helen Walker-Hill said it best: “Her remarkable career began before the civil rights era, while de facto segregation was still the norm in the North as well as the law in the South, and black performers had difficulty gaining access to opera houses or concert stages. By midcentury she was acknowledged as one of a handful of significant American composers, whether black or female, whose music not only was performed frequently in Europe and the United States, but also was published and recorded. She drew on the strengths and musical traditions of her African-American heritage, competed successfully in the white mainstream musical world, and gained an international reputation as a composer of undisputed talent and skill in an eclectic twentieth-century musical language. This achievement was not only impressive but also subversive; a challenge to the status quo without being intentionally political…Her tenacity and perseverance in continuing to compose and to pursue performances and publication, despite ill health, social and political upheaval, public ignorance, and rejection, is deeply moving and inspiring.” Happy 100th, Julia Perry! - Ashleigh Gordon Artistic Director Well, as the saying goes, all good things must come to an end. As I write this BIBA blog post, I have come to the end of my term as the 2022-2023 Shirley Graham Du Bois Creative-in-Residence. This last year has been amazing in so many ways, and working alongside Castle of Our Skins on poetry, music, Black history, and arts programming has been incredibly rewarding. I had the opportunity to close out my time as Creative-in-Residence in the best way possible: with a Harlem Renaissance-inspired rent party fundraiser on Friday June 30th. In my previous BIBA blog, I talked about my research on Harlem Renaissance literature and culture and how I have specifically focused on the underground culture of house-rent parties in the 1920s for the last six years. Rent parties were Black Harlem dwellers’ response to exorbitantly high rents and low wages during the Great Migration at the turn of the 20th century. They’d host strangers and friends in their apartments, charging each person a small entry fee to enjoy music, food, and dancing for the night. The money raised would go towards the host or hosts living expenses for the month. In that same spirit of community economics and joy, Castle of Our Skins and I had the idea to host an event to raise funds for a Boston-based organization, and that organization was the League of Women for Community Service. The League has been around since 1920 hosting Black women boarders affected by segregation and prominent Black women such as Marian Anderson and Coretta Scott (eventually -King) on their visits to Boston. Their headquarters at 558 Massachusetts Avenue is currently undergoing renovations, and we wanted to support their efforts to preserve this historic space that houses a treasure trove of archival materials from photos to correspondences to art. Last Friday night at Black Market Nubian in Roxbury, Castle of Our Skins and I brought together a two-piece band featuring musicians Kevin Harris (piano) and Ivana Cuesta Gonzalez (drummer) of the Kevin Harris Project, dancer Aysha Upchurch, VLA Dance, orator Regie O’Hare Gibson, and yours truly sharing poetry. It was a beautiful night of community, food, mocktails, music, dancing, and raising funds for a wonderful cause. What I felt in that space had to have been similar to what those 1920s Harlemites felt within the walls of their small apartments and rooms—sociality, joy, inhibition, freedom, and pride. I saw people laughing and moving their feet and hips and enjoying the improvisational vibes offered by the band and the dancers. I saw them savoring delicious food and drinks. I saw them being moved by the words shared onstage, and I saw them having carefree fun with our step-and-repeat photobooth. We captured the essence of the rent party tradition in those few hours by simply honoring history and honoring one another, and we were able to put our resources together to aid the League in its ongoing work.

I’d like to end by saying that I couldn’t have imagined when I was selected as the Creative-in-Residence last summer I would help make something as magical and beautiful as this rent party was manifest in this way. I have to give a sincere thanks to Ashe Gordon, Kelley Hollis, Anthony Green, and the entire Castle of Our Skins crew for their care and attention to every idea I offered to them and to every part of me as an artist and researcher. This year with COOS has been an absolute dream. I am walking away from this residency with so much joy for what we accomplished together and with abundant hope for the future of COOS, for all of the artists I have connected with in Boston, and for my own continued research and meditation on Harlem and black life. --Angel C. Dye Chevalier the Film in Review by JeanCaleb Belizaire & Ashleigh Gordon

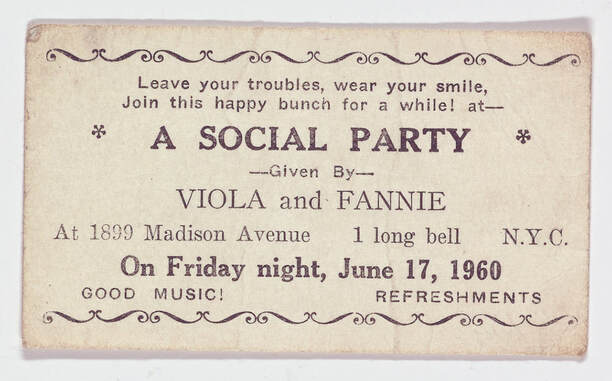

(Achtung! Spoiler alerts ahead…) What was the vibe of the room? - JeanCaleb On Wednesday April 19th, I had the pleasure to see Chevalier at the Coolidge Corner Theatre. The Theatre had a very old-timey, vintage vibe to it which I enjoyed. There was a string quartet playing Chevalier’s music as people were walking in, this sort of set the tone for what we were about to watch. Someone behind me even mentioned that this is most likely how the music would have been received back then, musicians playing while the audience mingled. I saw people from all walks of life in the audience, the majority being a mix of older white people and adult black people. Was the movie historically accurate? - Ashleigh Not entirely (which is understandable as it’s not billed as a documentary). Did I mind? Not really as I could understand the narrative reasons for the historical revisioning. While an epic musical sparring battle between Mozart and Chevalier didn’t really happen, Chevalier did champion the sinfonia concertante, a concerto featuring two soloists and orchestra. (Fun fact: Chevalier wrote eight of these kinds of works between 1775 and 1778 to Mozart’s one composed in 1779. They were so notable that Mozart copied a musical passage from one of Chevalier’s scores, hiding his thievery only through a half-step transposition). The prelude scene also gave a nod to the diminutive historical narrative placed on Chevalier as being a Black “second fiddle” to Mozart’s dominance. In the end, Chevalier’s skills speak for themselves and place him defiantly in a category all his own. Another revisionist element that became a central aspect of the plot was his relationship with his mother Nanon. A Senegalese woman enslaved by the white plantation owner George Bolonge, Nanon was brought to France in 1753 along with Chevalier (and George’s wife and legitimate child). While the movie chose to dramatize their separation, I could fully understand the narrative reasons for doing so. As Nanon ultimately represented the African cultural roots, language, and traditions that we (the audience) could tangibly see, it made sense to represent Chevalier’s removal from those roots with an actual forced, physical separation. Nanon became a voice of reason - an ancestral reminder - that grew louder in Chevalier’s mind, helping him to see the dichotomy in which he exists: a Black dot in a white space. So whatcha think? - JeanCaleb Overall, I loved the movie. It explores many themes that I can personally relate to; for example, the movie touches on W.E.B. Dubois’ double consciousness, the idea of being Black in a white dominated world or space, having to constantly code switch and feel like you can never really be your authentic self is something that me and so many other black people in America can relate to. One interesting example of this is when Chevalier’s mother and friends were speaking their language in Chevalier’s house, you can tell how uncomfortable he is by this and tell them that French is the preferred language. To me, I feel like his reaction comes from a place of insecurity, he doesn't really feel connected to his mother who represents his roots and his people. Showing how isolated he might’ve felt throughout his life. Feeling like he doesnt belong with his own people, or French people. Another aspect I enjoyed was this nursery song Chevalier’s mother sang to him as a child. She brings it up again later on when she moves back in with him, asking him to play it for her and how it would be a great addition to his opera. He denies this idea, he denies his past, his heritage. Later on in the movie towards the end in the Last scene, we hear that same melody incorporated into Chevalier’s composition. Symbolizing how he has come to terms with his heritage and background and learns to embrace it in everything he does. Any takeaways? - Ashleigh I was elated in the final moments before the credits when they relayed Chevalier’s legacy. How racism and the power struggle that drives slave systems overshadowed his lasting impact. While France would abolish slavery in 1794 (five years before Chevalier died), Napoleon would reinstate the harsh system of Code Noir in French Colonies in 1802 (three years after Chevalier died and during the Haitian Revolution, which was fought between 1791 and 1804). Napoleon would intentionally ban his music, effectively wiping his pioneering sinfonia concertantes, violin concerti, symphonies, sonatas, operas, etc from stages and history books for centuries. It would be about 130 years after his death before a string quartet by a Black composer - the late 19th century born African American composer and violinist Clarence Cameron White - would have a string quartet performed in Paris (one that ironically was unabashedly inspired by Negro melodies). What drives this point home even further was that Chevalier was pivotal in bringing the medium of string quartet writing to France during his lifetime. Its popularity to French audiences was a result of his work. Through power, intentional erasure, and racism, Chevalier’s prolific voice and fullest potential were stunted. With optimism, we have the ability to ensure that history will not repeat (or rhyme) and let a similar fate of forced amnesia befall yet another Black mind. When I was named this year’s Shirley Graham Du Bois Creative-in-Residence, I thought seriously about how I could bring my creative work as a poet together with my research in African American literature and culture. Thankfully, it has been a very organic pairing as I’ve spent the last almost six years researching and archiving on the house-rent party tradition of the Harlem Renaissance in the 1920s. In 2017, I began a deep dive into rent parties after coming across a Slate article on Twitter about Langston Hughes’ collection of rent party invitations, which are a part of his papers in the special collections at Yale’s Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscripts Library. I was amused by the cheeky, rhyming phrases on the cards like, “Hop Mr. Bunny, Skip Mr. Bear, / If you don’t dig this party you ain’t no where!” When I eventually got to the Beinecke to see the collection for myself, I discovered that it is large. The invitations, which for the most part are the size of business cards, have dates printed on them from 1927 to 1960. Hughes was an archivist, and he realized the cultural import of the rent party phenomenon so much that he saved a ton of invites in his papers. For his meticulous archival practice, I am grateful. House-rent parties, also called social whist parties, breakdowns, struggles, and a host of other colloquial names, were the turn-of-the-century iteration of southern jook joints and church socials. In the south, black people created spaces for dance, music, enjoyment, and pooling their resources when they had leisure time from their sharecropping labor. When black people migrated en masse from the south to the industrial north during the Great Migration of the early 20th century, they took with them the jook joint and church social ways of knowing. They were faced with a housing crisis in New York specifically: limited housing options, dilapidated buildings, and disproportionately low wages and high rents compared to white families. And so the rent party—hosting people in one’s apartment and providing music, southern food, and good vibes for a small cover charge—became not just a means to an end but a way of continuously cultivating joy and centering pleasure in a time of serious economic, social, racial, and environmental disparities. Rent parties were so ubiquitous and so much a part of the fabric of 1920s Harlem because they were semiprivate and semipublic, they were safe spaces for nonbinary and nonheteronormative gender and sexual expression, and they were the places where jazz music had its origins alongside numbers running and other “underground economies,” as LaShawn Harris terms them.

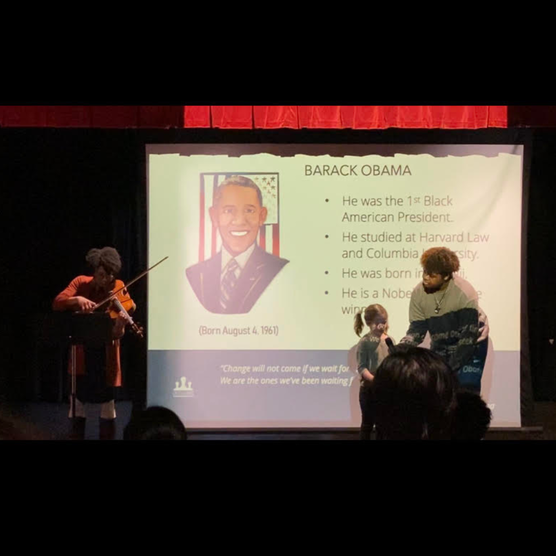

Langston Hughes’ extensive collection of rent party invitations gives insight into just how longstanding a tradition rent parties are. Katrina Hazzard-Gordon says that, like many things still present in our culture, rent parties can be traced back to plantations of the antebellum south where enslaved people were resigned to organizing covert recreational and social gatherings from church services to celebrations to avoid the watchful eyes of their masters and overseers. Hazzard-Gordon argues that this secrecy, or at least the practice of gathering without white presence or control, carried over into the post-Reconstruction period. My fascination with this understudied tradition of rent parties and community economics comes from both the insistence on black joy that they represent and the longevity of their presence in the real world and in media. In the 2002 quadrilogy film Friday After Next starring rapper Ice Cube, he and his cousin throw a Christmas rent party to avoid being evicted after their apartment is burglarized and their rent money stolen. In season two of the Hulu original series Woke, character Ayana throws a 1920s-inspired rent party to save her indie magazine’s office, which has been doubling as her apartment while she’s low on cash. There are numerous other popular culture remnants of the original rent party tradition. And there are black communities, like The Salt Eaters Book Shop (aptly named after Black Feminist author Toni Cade Bambara’s powerful novel) and its followers in Inglewood, California, who recently hosted a Beyoncé RENAISSANCE-themed rent party that went over so well, they’ve come back with a Sade-themed party and have plans to keep the gatherings going. The rent party’s legacy continues to uphold and uplift black folks over 100 years later, and I see it as a model for how we might all approach community care, subsistence, and joy. This is all to say that I’ve truly fallen in love with the history and culture of rent parties the more I have researched and learned about them. Black people’s innovative ways of being in a very antiblack world never cease to amaze and inspire me. We have working-class black folks of the Great Migration to thank for what we now know as jazz, and how beautiful is that? People working the most backbreaking and low-paying jobs as domestics, shoe shiners, and porters found the strength and energy to create the spaces that allowed improvisation and musical genius to flourish. Their contributions of living and being changed the world, and my hope is that the research I do and the upcoming Harlem Renaissance (and yes, rent party!) collaborations I am curating with Castle of Our Skins will honor these brilliant people and carry on their spirit of togetherness and uninhibited enjoyment. -Angel C. Dye My name is JeanCaleb. Some of you may know this already but I’m doing an internship at Castle of our Skins through June. I’ve been working with COOS for a little under a month now designing social media posts, researching, and performing. On February 12, I had the opportunity to be a teaching artist along with COOS’ founder and Artistic Director Ashleigh Gordon presenting “A Little History” for an audience of tiny humans at Boston's Children's Museum. A Little History tells the simplified stories of nine legendary figures in Black History: Phillis Wheatley Peters, Garrett Morgan, Madam C. J. Walker, George Washington Carver, Margaret Bonds, Ed Bland, Angela Davis, Bayard Rustin, & Barack Obama. Through original music, poetry and interaction, students are encouraged to get up and move, sing, clap, invent, and play make-believe as they learn about these historic individuals. I learned recently that this was COOS’ signature piece; premiered back in their first season; written by Associate Artistic Director Anthony R. Green for Ashe to perform for school groups. It’s been performed for hundreds of students in their past 10 seasons. In preparation for our performance Ashe and I rehearsed together. First looking at the music it didn't seem hard. I was immediately humbled, however, by Ashe who put a tuning app on for me to play with. It made me realize my intonation needed some help, to say the least. After this, I downloaded that same app and drilled the pieces with the tuner to get more confident. When I arrived at the BCM I got my name tag and met up with Ashe who was a short walk away from the door. We talked a bit then she introduced me to our contact at the museum. My mom met up with us eventually after she found parking. It was about 25-30 minutes until the show. We were shown to the green room which was just a side room near the stage. As I unpacked and tuned, Ashe got situated with her mic and slides. Once she was done she also unpacked and tuned.

We went through the show for an audience of my mom,Vaughan Bradley-Willemann , and another lady (that I learned later was museum president Carole Charnow). The run-through went well, though it was a bit awkward for me just because it was a new space and I didn't really know how my sound should adapt to it. However after a few minutes of playing I was fine. As the clock was counting down until doors opened, my hands started to feel cold, which was normal for me before I performed. Ashe gave me a little pep talk about how her hands also get cold and we warmed our hands together for a while as people started to come in. As we walk on stage I start to feel less nervous. It wasn’t a huge venue and the crowd wasn’t crazy large. We got through the first piece and it was okay. Some of the younger kids were making noise and just being kids so that was kinda distracting. At some point during the transition between one of the historical figures and the next, I had to set my instrument down off stage. When I went back to grab it, I plucked the strings just to check and of course my instrument somehow got out of tune while it was sitting there. The show was still happening next to me, and I didnt want to make a lot of noise. I desperately tried to get my viola in tune but it was just not working. I went on stage, viola still not tuned, when Ashe saw me struggling. She offered to switch roles, with her playing my part and me helping with the children. We got through it and the rest of the show went smoothly (thank god). To be honest, I was a little hesitant to accept this performance offer only because I have trouble connecting with small children. They're so unpredictable and squirmy; it makes me all weird and awkward and it’s hard to interact. But, I think this performance was a stepping stone for me in a way, even though I still feel the same way about kids as I did before. Now that I have this experience working with them, I feel like my next experience will be so much better. It was an honor to perform with Ashe and I'm so grateful to her and everyone at Castle of our Skins for giving me these amazing opportunities. I look forward to the next few months working with them UPDATE: The submission deadline has passed. Thank you to everyone for submitting! If you'd like to receive updates about our next call, please subscribe to our mailing list.

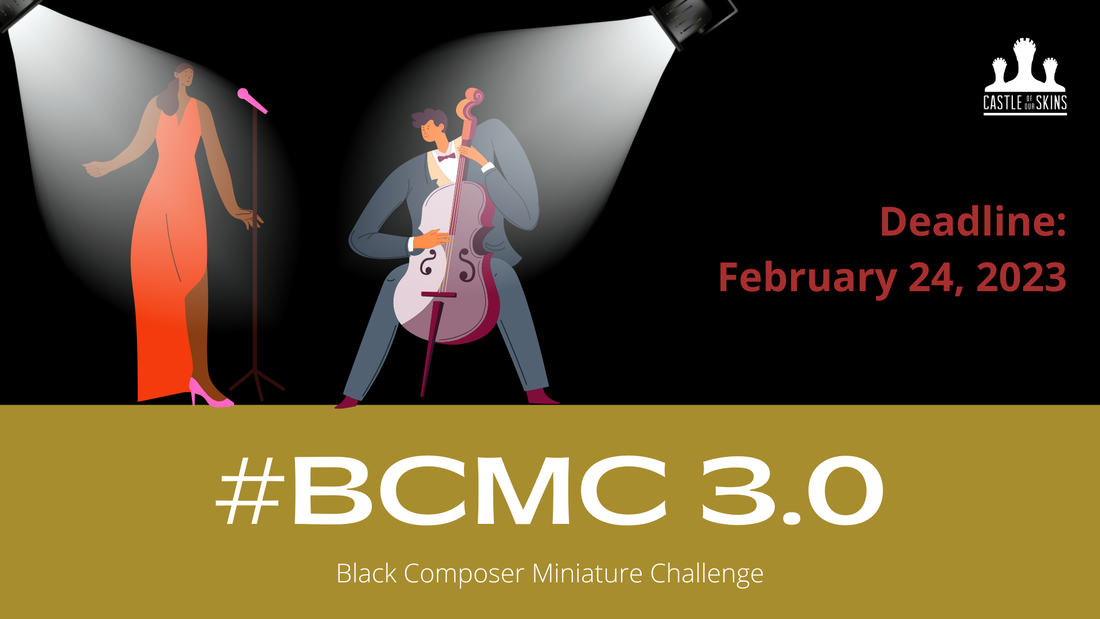

Castle of our Skins announces part three of its #BCMC – Black Composer Miniature Challenge! Composers who identify as Black and part of the African diaspora are challenged to compose pieces for soprano and cello! Each piece must be 30 seconds (give or take) or less. For #BCMC 3.0, composers who plan on setting text are asked to use a haiku and/or tanka from the Castle of our Skins' Black Poet Miniature Challenge (#BPMC) project! Details for this year’s #BCMC 3.0 are below! Welcome back to BIBA! Today I have the pleasure of sharing a recent interview with our 2022-2023 Shirley Graham DuBois Creative-in-Residence, Angel C. Dye! Angel is a poet, a publishd author, an HBCU grad, PhD candidate, and lover of all things purple! Get to know Angel and enjoy!

BIBA: Can you talk about your journey to becoming a writer; how you got started and/or if you had a particularly encouraging mentor that set you on the path? Angel: I remember picking up a pencil to try my hand at creative writing at about 10-years-old. I was a voracious reader as a pre-teen and teenager (this has carried over into adulthood in more ways than one), and I did my best to imitate the novels I was reading at that time. As I approached middle school, I somehow found my way to slam poetry. I've never considered myself a slam poet, but I would spend hours on YouTube watching Def Poetry Jam and Brave New Voices competitions, and the young poets on there were close in age to me. I thought, 'These are my people. I want to do what they do, make something impactful out of words.' A lot of life transitions happened for me as a pre-teen and teen--moving states and starting new schools, experiencing eviction and homelessness--and all of those scary and difficult things led me to writing. I wrote and entered contests at school and won some of them and realized that poetry was something I both needed and enjoyed. In college, my amazing mentor, Dr. Shauna Morgan, encouraged me to go all the way with poetry. She saw potential in my writing and my academic performance and really inducted me into a community of writers and scholars that I am still very much a part of. I have her to thank for so much of who I am." BIBA: Can you share a bit about your creative process? What's your ideal creative environment? Angel: One thing that my friends and colleagues can attest to is my seriousness about the color purple. I have purple items around me at all times because the color inspires me so much, and I have taken some subconscious vow to only write in purple ink. It has become a personality trait at this point! Ha! Aside from that, I am a night owl and I often write and journal and pray late at night. It is quiet and still then and all of the day's events are present with me, and somehow that often brings forth new ideas. I have never had a strict writing schedule because poems do not flow to me that way; they come when they are ready, usually without warning. My iPhone is always near and so is a pen because sometimes a poem or a fragment will nudge me when I am waking up or showering. I try to listen in those moments and allow whatever words are beckoning me to just come without forcing them or trying to make them neat and perfect." BIBA: You wrote a book! I just ordered (Order Breathe from Central Square Press). It seems like Breathe was an outlet to work through some difficult things and attempt to heal. Can you talk about how that came about and maybe any surprising discoveries along the way? Angel: Thank you so much for supporting my work! That always means so much to me. Breathe was certainly a very raw and unfiltered offering in a lot of ways. What many people don't know is that that collection is not a set of poems I wrote and published in 2021. It was released in fall 2021, but the poems are pieces I've written over the last five years or so. My wonderful publisher at Central Square Press, Enzo Surin, reached out to me after I finished my MFA in 2019 and just encouraged me to gather up the poems I had been working on over time and see if they fit together in an organic way, and they did. I shared poems about my experiences with sexual violence and poverty and an incarcerated father in Breathe, and I was afraid. Afraid that I was exposing too much, afraid that there would be backlash, afraid that people would look at me differently if they knew how many scars I'd been hiding. What I learned is that people appreciate, and even admire, honesty more than anything. The collection was not met with judgment at all. It was met with care and affirmation and love. Folks relate to the experiences I shared, and for me that makes my vulnerability worthwhile. To know that the meaning-making I am attempting to do as a poet is resonating with people is very rewarding and it motivates me to keep digging deep. BIBA: How did your experience at Howard, an historically Black university, inform your artistry? Angel: This is such a fitting question just after our first in-person Howard Homecoming in two years! My love for Howard can't even fully be put into words. I struggled a lot there. It was an uphill battle financially to finish my English degree. And yet, I had the time of my life there. I was "nurtured in love," as one of my former professors says of my experience at Howard. Howard is where I first began to identify myself as a poet. I was writing before I got there, but it was there that I read and learned about this long legacy of black artistry and creativity that defines people of the African diaspora, and I began to see myself as part of that. I was reading Robert Hayden and Amiri Baraka and Lucille Clifton and Sonia Sanchez in my classes, and I was performing my own poems at open mics and hosting a monthly open mic at my local coffee shop job. Howard is called "The Mecca" for a reason. There you are surrounded by intelligent, beautiful black people from every corner of the world and you realize that you are being prepared to live in a world that doesn't always look like that, but you leave Howard with enough self-confidence and knowledge and community to know that you'll be alright even when you are the only person who looks like you in the room. BIBA: How did you hear about COOS? Angel: Like so many things in my life, COOS came to me in a very full-circle way. I met opera singer, composer, and musician Dr. Tanyaradzwa Tawengwa in fall 2018 while we were both in graduate programs at the University of Kentucky. Our sisterly, scholarly, and creative connection was immediate. We have since collaborated on performances and art and really built a network of artists and friends around us. In 2020, Tanyaradzwa became the inaugural Shirley Graham Du Bois Creative-in-Residence with COOS, and she brought her unique musicianship and style and grace to the role as she does with all things. It was she who strongly encouraged me to apply for this year's residency. I actually told her that I didn't think I was qualified. She literally scoffed! Thank goodness for her encouragement and faith in me and in my art. I would not have the honor of serving in this capacity if not for her and the pathway that she has forged. I am beyond grateful and excited to be collaborating with COOS over this next year, and I look forward to all of the art we will make and all of the fun we will have doing it! |

Details

Writings, musings, photos, links, and videos about Black Artistry of ALL varieties!

Feel free to drop a comment or suggestion for posts! Archives

May 2024

|

Member Login

Black concert series and educational programs in Boston and beyond

RSS Feed

RSS Feed