|

by Liz Gre Hey BIBA readers! I’m so excited to be a new contributor to this blog! It seems to me that collaboration between visual artists and sound artists is taking over the landscape in the art world as a whole. While the environment can still feel quite separate (painters here, singers there, composers somewhere in a dark corner yelling at Sibelius…no shade…) artists are incorporating "multi-sensory" in new and exciting ways. This is not a new concept. Multidisciplinary artists from Maren Hassinger to Sanford Biggers have dissipated any sense of barrier between their installation work and their performance. I’m particularly intrigued with how multiple artists come together to create collaborative multi-disciplinary work that honors the practices of all artists involved. From the beginning, Black artists of all disciplines have stretched our imaginations with exciting, feeling-forward, sometimes tough, and critical works. So for my first BIBA series, I’m focusing on connections that have been forged between visual artists and sound artists (of all leanings). First up - Alexandria Smith! In 2019, I was commissioned by Visual Artist Alexandria Smith to collaborate on an installation at Queens Museum (NY). Alexandria has had a stellar rise in the last 3 years, with shows of her work in all corners of the United States, London, the Netherlands, and Italy. She is the recipient of numerous awards and residencies, including most recently the Queens Museum | Jerome Foundation Fellowship; MacDowell, Bemis, Yaddo and LMCC Process Space residencies; a Pollock-Krasner Grant, the Skowhegan School of Painting and Sculpture Fellowship, the Virginia A. Myers Fellowship at the University of Iowa, and the Fine Arts Work Center Fellowship from 2013 - 2015. Her recent exhibitions include a forthcoming solo exhibition at the Queens Museum; the first annual Wanda D. Ewing Commission and solo exhibit at The Union for Contemporary Art in Omaha, NE; a traveling group exhibition called “Black Pulp” at Yale University, International Print Center NY (IPCNY), USF and Wesleyan University, and a commission for the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture. Her work is currently included in "The Lure of the Dark: Contemporary Painters Conjure the Night" at Mass MoCA. BIBA : Your practice has taken a journey from illustration to installation. If you could, describe how external influences have impacted your practice. AS : Initially, I wanted to be an animator and comic book artist, which then lead to illustration, all of which are dependent on audience engagement. It seemed like a natural progression for my practice to evolve into painting and then installation. My engagement and eventually audience engagement became integral to my practice. A lot of the visual artists and musicians that inspired me early on in my artistic development such as Kara Walker, Wangechi Mutu, Janet Jackson, and Traci Chapman had an investment in the audience that moved me to desire the same in my work. BIBA : It seems that you take a liking to storytelling. What were the stories/fables/folktales that have shaped your growing? AS : Parallel to my desire to be a visual artist was also a strong interest in fiction writing. I was always an avid reader, especially of the magical realism genre, fantasy stories, and fables, specifically Aesop’s Fables, African/Southern Black folk tales, and later Toni Morrison novels were instrumental in my artistic development. I was fascinated by the ability of writers to provide insight to parallel worlds within these stories. Our reality was simultaneously happening alongside this fantasy world of absurdity. BIBA : How do you think Black music has shaped your artistry? AS : Black music provided me with the tools to understand how to emotionally and psychologically move an audience and tap into their innermost desires and feelings. This is something that I strive for in my own work, which is probably why I have moved towards more immersive ways of working. There’s something sensorial that you experience when you listen to music that cannot be replicated with visual art. I believe that’s the reason why creating has become so collaborative and interdisciplinary. BIBA : You recently collaborated with me (:-D) to create an installation for Queens Museum, Monuments to an Effigy. What led you to include experimental new music with your installation? AS : I have always wanted to collaborate with a musician and this exhibit in particular desperately needed to include all sensorial elements. I wanted visitors to the museum to be captivated by the sound first, and then feel its visual impact. Another personal reason, which I rarely share is that my dad is blind and has been for the past 10 yrs. It has been frustrating for me as a visual artist to share my work with the world when my father can’t actually see it. My knowledge and love of music has come from him, and it was important for me to bring that inspiration directly into my practice. I would wake up every Sunday to music blasting from his extensive collection of records which he would play all day long. It is a tradition that I carry on today in my own home. In many ways, I partly wanted to pay homage to my dad by creating an exhibition that he didn’t have to see in order to feel. Bringing him into the space and allowing him to touch the walls, feel the sculptures and hear the music was an incredibly moving experience for both of us. The music was my way of connecting with him, with you, and our ancestors. It was my way of providing access in all its forms, which has become important for me to continue in my work moving forward. BIBA : If you could collaborate with any musician, alive or ancestor, who would you work with and why? AS : I would collaborate with Prince. Prince’s ability to move through styles of music-making and performing, captivate a crowd and still maintain autonomy and freedom within an industry that historically has eaten up and spit out Black musicians is what I strive to achieve in my own practice as a visual artist. I truly believe that if Prince had decided to collaborate with a visual artist, it would have yielded an innovative and unique approach to creating unlike anything that we have experienced. The Incognegroes 60 x 72 in acrylic, oil and enamel on canvas 2018 courtesy of the artist To learn more about Alexandria Smith, please visit her website at www.alexandriasmith.com and follow her on Instagram: @alexandriasmithstudio  (photo by Sarah White/Fotos for Barcelona) Liz is a composer and vocalist writing strange, experimental, ethnographic compositions with Black Women for Black Women. In 2017, she performed the title role in Mother King, an opera about Alberta Williams King (the mother of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.). She was a 2019 Inside/Outisde Fellow at The Union for Contemporary Art (Omaha, NE). Currently located in London, UK, she is working towards her MPhil/PhD in Music at City, University of London. Social Media : IG/Twitter - @lizgrelizgre

1 Comment

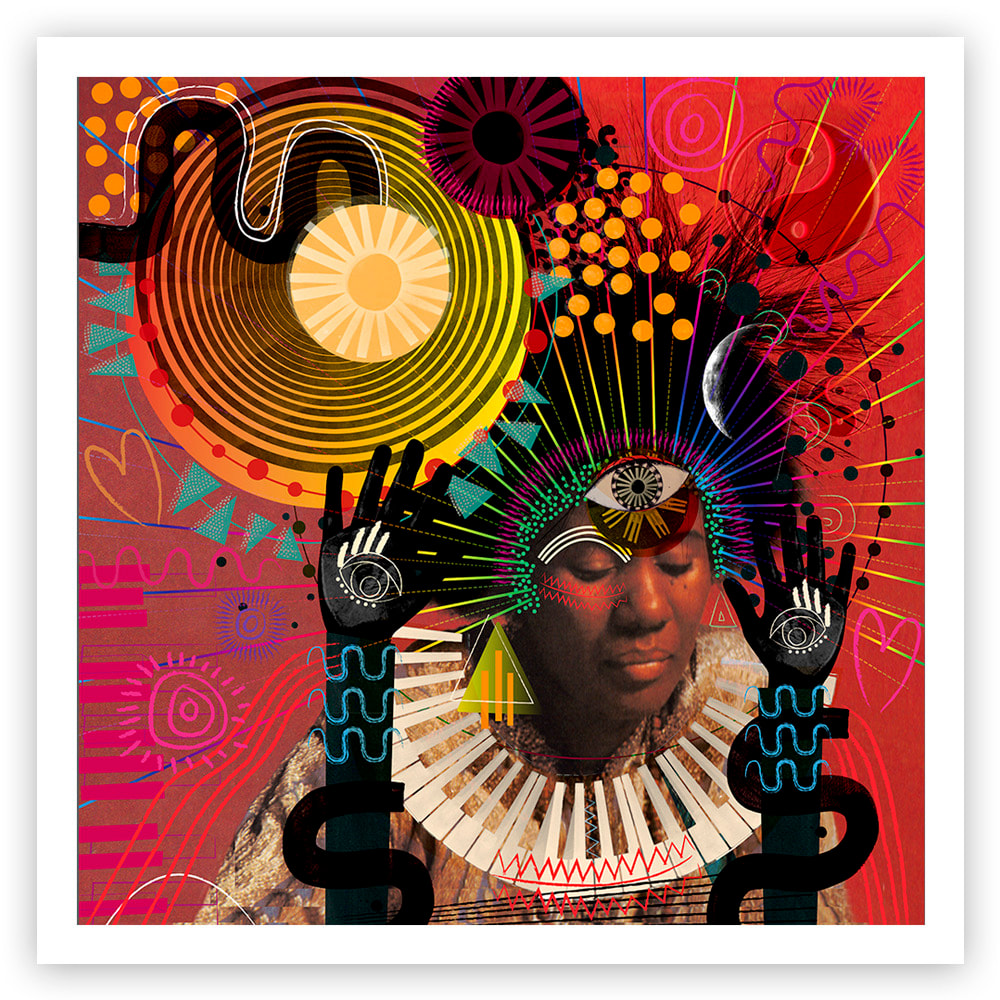

by Shannon Sea When people think of Alice Coltrane, they often remember her as a celebrated jazz composer and musician. She, indeed, was a virtuoso on the piano and harp. She replaced McCoy Tyner as John Coltrane’s pianist, and later developed her own sound that infused improvisational jazz with harp and spirituality. People also remember Coltrane for her devotional music, which comprised ambient synth soundscapes, harp, vocals, organ, and Hindu chants. Yet, many overlook Coltrane’s avant-garde classical pieces, which incorporate strings, harp, synthesizers, and Messiaen-like extended techniques. Furthermore, little is regarded about Coltrane’s re-interpretation of Stravinsky’s Firebird and Rite of Spring. She said she was inspired to rework those pieces after Stravinsky spoke to her in a dream. (Art/Image by Victoria Topping) I would like to bring your attention to Radhe-Shyam, one of my favorite classical pieces by Coltrane. Radhe-Shyam begins with strings playing a dissonant chord. Coltrane then swiftly enters with her electro-acoustic harp, and immediately the music draws you into another realm -- into a spiritual hyper reality. A lush counter-melody ensues as the strings gradually shift from one dissonant chord to another, and Coltrane dances with her harp. Coltrane’s melody is modal, and evades a tonic center, which gives the listener an other-worldly feeling. In Radhe-Shyam, Coltrane uses silence perfectly, as she creates space for her ethereal harp solo. The strings re-enter in stark contrast, and then break out into Messiaen-like bird calls. The piece then ends without explanation or apology. Radhe-Shyam has haunted me since the first time I heard it. There was something so distinct about every part of it, especially the string orchestration. As I inquired more about Coltrane’s composition techniques, I learned that she defied the traditional balance of string ensembles in order to create her own sound. For instance, on Radhe-Shyam, the string section consisted of three violins and one viola. Coltrane is one of my favorite composers, and her music is authentic, spiritual, and intellectually sophisticated. I hope you will discover more of her string compositions on her albums Transcendence and Eternity.

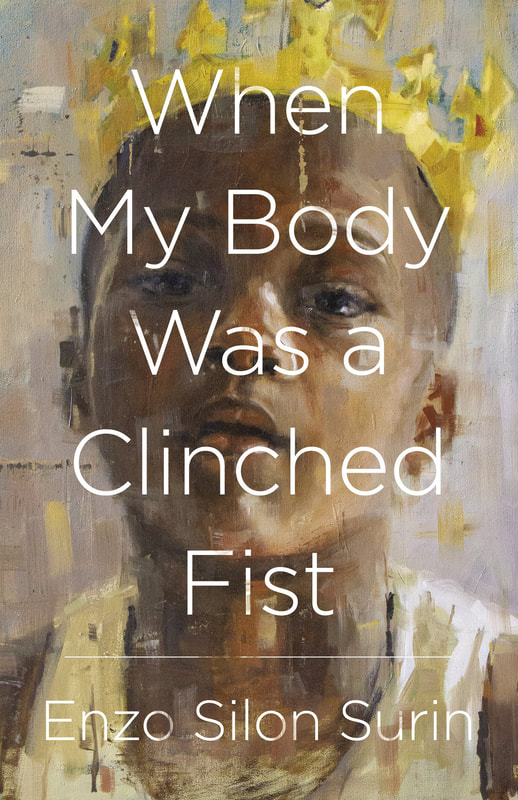

by Ashe Gordon Happy Sunday, COOS and BIBA Fans! Today's BIBA Blog features the Haitian-born poet, educator, publisher, and social advocate, Enzo Silon Surin! He is the author of When My Body Was A Clinched Fist (Black Lawrence Press, July 2020), and the chapbooks, A Letter of Resignation: An American Libretto (2017) and Higher Ground (2006). He is a PEN (Poets, Playwrights, Editors, Essayists, Novelists) New England Celebrated New Voice in Poetry, and the recipient of a Brother Thomas Fellowship from The Boston Foundation and a 2020 Denis Diderot Grant as an Artist-in-Residence at Chateau d’Orquevaux in France. Surin’s work gives voice to experiences that take place in what he calls “broken spaces,” and his poems have been featured in numerous publications and exhibits. Explore more in his interview below! photo by Richard Howard BIBA : You were born in Haiti and lived in New York among other places. How did/do those two worlds shape you and your creative practice as a poet? ESS : The introduction to OutKast’s sophomore album ATLiens is a track titled “You May Die.” The album signified not just a new era in hip hop but in my life as well. I spent most of my childhood being alienated from self, from homeland, in a place that was supposed to be a refuge. As a Haitian-born poet, I immigrated to the United States at a young age, fleeing a country littered with political violence and landing on the shores of another country with just as much social violence. I spent most of my days in Jamaica, Queens, thinking any day was going to be the day that I would die. You can charge that to being a refugee, to New York City streets or to the police that patrolled them. The only safe place was the retreat of my own mind and body. Which eventually led to the discovery of the page as a safe place to frame and tell stories about my experiences. I started to write poetry as a way of expressing my emotions and as a way of getting through the day. It was a matter of survival, really. Being a product of two countries, I drew from my Caribbean roots and our penchant for telling stories and mixed that with the rhythm and cadence of my new country’s burgeoning hip hop culture. And since English was my third and not my first language, I fell in love with the process of trying to find the right combination of words to be able to tell an effective and compelling story. To this day, I consider the dictionary and thesaurus to be a poet’s best friend, and the page is still a very safe place for me. BIBA : You describe your work as amplifying experiences that take place in “broken spaces”. What do you mean by this and can you give an example of a "broken space"? ESS : When I write about broken spaces, which is a term borrowed from Afaa Michael Weaver’s poem “Blues in Five/Four, the Violence in Chicago”, I mean the places that most of us would rather forget. I am referring to the crevices that Black and brown folks often fall into, the cracks of society, the wrinkles & folds, the corners and other spaces we call home, only to be traumatized within them or forced to live out past traumas. These spaces are also often forgotten places that have collapsed over time, which means that some of the people who inhabit those places are also out of sight and out of mind. In other words, no one is really checking for them under the rubble. Yet, within these same spaces, people make a living, make a way out of no way, make the best of each day by writing or rewriting the narrative of their demise. These are the experiences that are amplified in my work and also in the work of the writers I publish through Central Square Press. An example of a broken place would the title poem for my forthcoming book, WHEN MY BODY WAS A CLINCHED FIST, which chronicled the years my mind and body endured while growing up in Queens, NY from the mid-eighties to the mid-nineties. When I was 13, I witnessed someone being beaten within an inch of their life over a glare. As a youth, I also witnessed odd exchanges between rival posses: sanctioned peaceful football games and fights scheduled at a specific time and location. The violence wasn’t always chaotic—sometimes, it was a methodical type of violence that was predicated on an odd respect for order—but more often then not, it would erupt like one held the balance of the universe within their fist. On the way to and from school, that’s the world I navigated. It’s the world I try to chronicle through the eyes of a little boy who spent 10 years of his life negotiating this terrain. That is still someone’s reality today and I’ll keep writing about it until we figure out a way to mend these broken spaces together. BIBA : What drew you to create your own publishing company, Central Square Press? ESS : The idea for Central Square Press was born out of numerous heartfelt conversations with my peers about the perilous journey to get their work out into the world. These folks were phenomenal poets, some with MFA degrees and beyond, who had very-little-to-no success finding a home for their book manuscripts. At first, I just wanted to create an opportunity for these poets to publish their work, you know; to provide one more entry point for manuscripts trying to make their way into the world. However, thanks to an organization that released a report with the acceptance rates of journals and publishers based on demographics, I was able to see the dismally low percentage of Black and brown writers being published, especially female writers. We decided to narrow focus and publish underrepresented writers, especially those whose poetry reflects a commitment to social justice regarding African American, Caribbean and Caribbean-American communities. In addition, the number of independent Black publishers is very low compared to what it used to be while hundreds of Black writers come out of writing programs every year. I was very conscious about needing to launch a small press by a Black publisher. The conversation in many circles I frequented rarely went beyond our roles as writers in publishing; it shifted from the lack of publishing opportunities to the creation of publishing opportunities. We often want to be published but not necessarily become those who publish other writers. As a result, we fall in line with a pre-determined path for publication, even when it doesn’t successfully serve us in a way that is always fruitful. That wasn’t always the case and I wanted to draw from the lineage of Black publishers who created opportunities for other Black writers. Cover art: “When I Ruled the World” by Carlos Rancaño

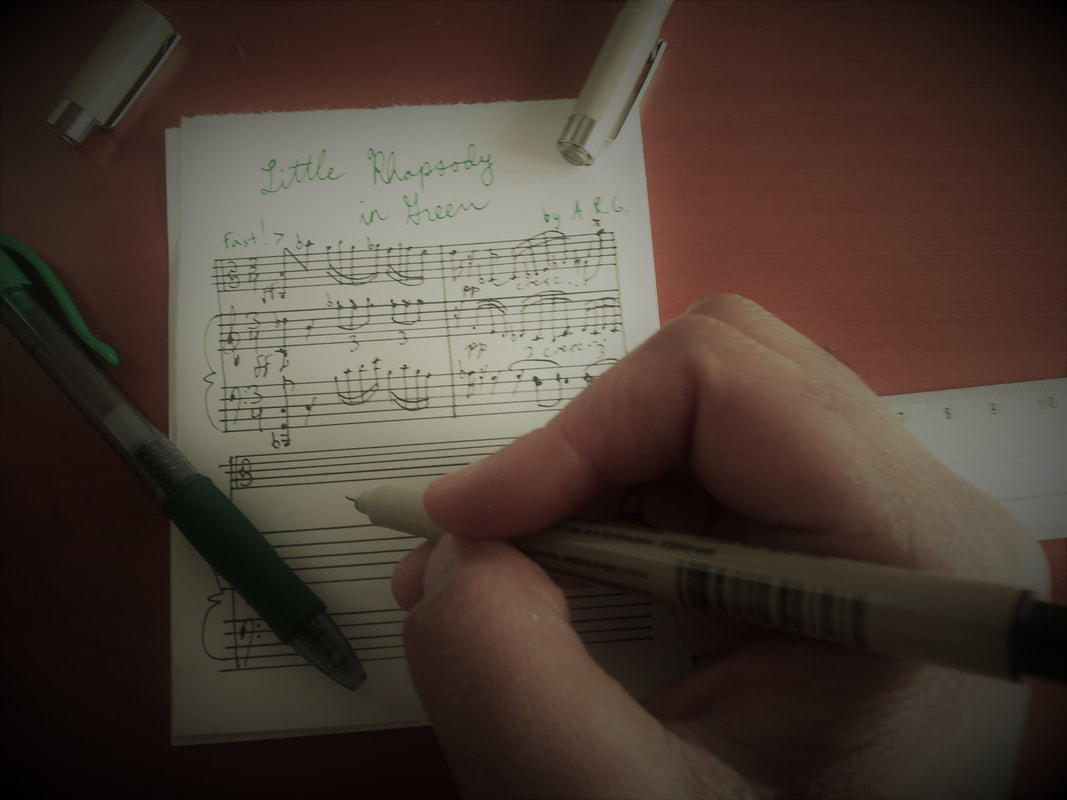

BIBA : As an educator, what are some of the tools you share with your students (or use yourself) to help craft a compelling story? Are they different for poems vs. short stories vs. non-fiction? ESS : I have dedicated my life and career to affecting social change through creative and critical writing. As such, it is important that my students are exposed to all the necessary tools available in the writer’s toolbox. Whether they are writing poetry, fiction or non-fiction, I always challenge my students to remember their goal—the point of writing the story—and whether their goal to write a compelling story has the reader in mind. One tool I often focus on in my creative writing workshops is something called the human scale. It is a term that I borrowed from the field of architecture, which is used the determine whether or not a particular design has considered actual human beings inhabiting the space. I use the term to remind my students that another human being will be reading their work and to always keep that in mind. Literary devices are tools to enhance a story and are not the story themselves. The average reader can tell when a writer is more in love with language than the story they want to tell. As such, my focus during the drafting process is to pose questions for them to entertain more than it is to provide line suggestions or feedback. I want my students to fully interrogate their own work before declaring a story or poem is complete: Have they left enough room for the reader to inhabit the lines of the poem? Have they considered the different ways a reader might enter a story? What hasn’t been said that needs to be said? What do you want the reader to walk away with? What will leave them satisfied or wanting more? With the last question, both elements are essential to writing a compelling story or poem. As a writer, one should always want a reader to feel full or wanting more but never satiated or famished. BIBA : Your new, full-length debut When My Body Was A Clinched Fist is a coming of age story "where hip hop and Haiti flow through the borough of Queens" (Tara Betts, author of Break the Habit). Can you share the process of working on this work, reliving moments from your childhood, and how that affected you as an adult today? ESS : The decision to write When My Body Was A Clinched Fist was not a complicated one, but it certainly was one of the toughest things I have done in my life. At some point, I realized the anxiety from which I suffered most of my adult life was connected to the pathology of fear I experienced as a youth. The collection was written as a way of coming to terms with what was a very difficult decade of my childhood in Queens, New York, one that would follow me well into adulthood. I wanted to chronicle the experience of growing up in an environment prone to social violence, where a simple walk down the street could lead to serious, and at times, deadly predicaments. However, I also wanted to address the human element in such circumstances and the versions of ourselves that are created when faced with these predicaments, and the sometimes detrimental effects of choosing not to participate in the violence. In a poem titled “My Body As A Clinched Fist”, I tell the story of what it felt like to watch a schoolmate get beat up by a mob simply because he looked at someone the wrong way. The incident happened when I was 13 years old and it had taken me almost three decades to be able to write about it. Such experiences were always readily available to write about, but in writing about them I would have to relive each moment. That type of emotionally challenging and creative work is necessary for a breakthrough, but it takes times—it took over ten years for the collection to come together. I am a freer and healthier person because of this book, and I hope it will help others to be a bit more free in their own lives. COOS INTERRUPTS YOUR SEMI-REGULAR SCHEDULED BIBA POSTING TO INTRODUCE ... THE BLACK COMPOSER MINIATURE CHALLENGE! #BCMC Composers who identify as Black or part of the African Diaspora are challenged to compose pieces for COOS co-founders Ashleigh Gordon and Anthony Green! Each piece must be 30 seconds or less. Pieces can be scored for:

- solo viola - solo piano - viola & piano duo Auxiliary instruments and other options may include: - voice (simple melodies, spoken word, percussive and other sounds) - various shakers, thunder tube, bird whistles, finger cymbals, 2 differently pitched singing bowls, a toy keyboard (only 4 notes at a time), a toy piano (25-key), common objects, Chinese toy pellet drum, a kalimba, and common objects (paper, pots and pans, sticks and stones, etc ... ) - simple electronic playback (no live electronics, please!) - piano 4-hand is also an option * if wanting to use auxiliary instruments or think outside of these parameters in any way, please consult with Ashleigh and Anthony at info [at] castleskins.org BEFORE starting your piece! Timeline: - Pieces are due May 1, 2020 by 11:59PM; early submissions are welcome and encouraged! - Depending on receipt and demand of the submissions, COOS will begin broadcasting virtual premieres of each piece starting May 15, 2020 (or later!) on COOS social media! Please feel free to share with friends and family! - Postings of the virtual premieres will continue for as long as necessary, but COOS will not take submissions after May 1, 2020, so get your pieces in! How to submit: - Please send your piece as a PDF and any necessary material for performance (parts, tracks, notation keys, etc ...) in any relevant format to anthony [at] castleskins.org - along with your piece submission, please send a creative headshot and a 100 word or less bio, with any social media handles/website links you would like shared. WE LOOK FORWARD TO PREMIERING YOUR MINIATURES! |

Details

Writings, musings, photos, links, and videos about Black Artistry of ALL varieties!

Feel free to drop a comment or suggestion for posts! Archives

May 2024

|

Member Login

Black concert series and educational programs in Boston and beyond

RSS Feed

RSS Feed