|

Happy Easter, BIBA Readers! Short post today; many musicians have been posting about their Holy Week gigs in churches all over the world. I wonder if any church is programming the Gospel Mass by composer/conductor Robert Ray? You can watch and listen to it below! Some may be wondering about the amount of improvisation in this particular performance. Well ... check out another performance of this massive, well-crafted piece, sung by a Polish ensemble, by clicking here!

And don't forget to attend next week's collaboration with Handel + Haydn, the upcoming project Nigra Sum Sed Formosa: I Am Black, but Beautiful!

0 Comments

Happy Sunday, everyone! Today's blog is a guest artist spotlight featuring the esteemed, world-renowned countertenor Reginald Mobley! After starting his classical music career as a member of the twice GRAMMY® nominated ensemble Seraphic Fire, Reggie has since appeared with Academy of Ancient Music, Agave Baroque, Bach Collegium San Diego, and The Handel + Haydn Society. With the latter, he had the honor of becoming the first Black person to lead H+H in its Bicentennial year. Recent festival appearances include Bachfest Leipzig, Festival Berlioz, Early Music Vancouver, Thüringer Bachwoche, and the Boston Early Music Festival. BIBA : How did you come into music and discover your preference for countertenor performance? RM : I think by now there's a common origin story for many Black American countertenors. Church choir ... gospel ... etc ... Mine certainly started that way in a small Seventh-day Adventist church in my hometown of Gainesville FL. That almost instinctual understanding and love for music was established there. I stayed interested in music, but it was never my first love. Not until I discovered Bach late in high school. It was a good thing, too. Circumstances (a sudden decision to attend an HBCU) put me in a position where I needed to decline an art scholarship, and I was able to secure a music scholarship that allowed me to study elsewhere. I was in music, but I spent years never really focused until I found myself back at home in Florida where my voice teacher at the University of Florida discovered my “real” voice. I honestly had no idea that countertenors existed, and had always assumed that those “mezzos” had strange masculine sounding names like Michael Chance and Andreas Scholl. When I made the switch, my professor told me it was this that I would do for the rest of my life. I've spent every day since trying to prove him wrong. BIBA : What have been your biggest visions for Handel + Haydn since you joined their team, and how have these visions or the planning for these visions unfolded? RM : It was strange happenstance that found me falling sideways into this role with H+H. Every now and then, it still hits me that this is even something I do. And when I found out I was the first Black person to ever lead the ensemble during the bicentennial year, the imposter syndrome certainly kicked into high gear. I'm not a conductor by trade, so I felt guilty that such an overdue milestone would be handed to me. However since then, I've come to really appreciate the trust that's been given to me, and I see how my particular perspective and outlook on life has something to offer. With that, I hope for two things to come out of my time as a director with H+H. From within, I hope to see more diversity. Not just in audiences, but onstage and offstage, behind the scenes. Not that the organization isn't trying, either. They're doing an admirable job. I don't know if any other period ensembles in North America are doing as much as H+H is to deepen diversity and fight against elitism built by years of cultural gentrification. But there's still very far to go, and the solution to the problem lies deeper than hiring a Black singer or instrumentalist. There has to be a stronger unity in purpose when tackling something as large as inequality in the arts. Not everyone needs to be focusing on the same tactic, I think. But there does need to be a cross-awareness of everyone's angles, so that we're all moving in the same direction. From without, I want H+H's presence in the community of Boston to be a stronger and deeper one. Often when I talk to a native and ask how they see this city, the most common response is that this is a sports town. Then, when I mention H+H and its long history of not just significant premieres, but the very deep connection to abolitionism and suffrage, it always comes as a shock. They never know any of this, and when they are informed, you can see the sense of pride dawning. They suddenly care a lot more about the role of arts in society, and are proud that something “Boston” is such a leader. I think our concerts help the regular Bostonian connect to the ensemble, and they learn how deeply connected we are to each other. But we can do more. Much more. And I feel it's our duty to root ourselves deeper into the current community. BIBA : Can you please discuss the upcoming "Nigra Sum Sed Formosa" project? How did it develop, and where does the name come from? RM : This Nigra Sum project came about as the result of a first time superhero team-up between H+H and Castle of our Skins. Ashe and I spent some time brainstorming a theme and a title, and it ultimately came down to us adopting the title of one of the pieces (perhaps the centerpiece) on the program. The piece, Nigra Sum, is a commission that was born from some of the racist actions and micro-aggressions that are heaped on artists of color. It came in a moment of frustration after an interaction with a well-meaning audience member, who commented again on the shock of hearing such a voice (my voice) come from a figure that is more in line with NFL field fodder. Even though this happens much more than it should, it only occurred to me then that this must be just as frequent with every other artist of color. So I sent out a Facebook status asking for stories, quotes, and anecdotes from every person of color who would be willing to share their experience to be used in a project. I then filtered and compiled many of these stories and situations into text form. At that point I thought about partnering up with a Black composer to see what we could make of it, and it was barely a moment that I realized it had to be my good friend Jonathan Woody. Jonathan is a gifted composer who has the added skill of writing quite fluently in earlier styles. (He’s also a damn good bass-baritone.) It seemed that for a lot of us, these racist encounters often happen right before we are to perform for these very offenders. So while they sit in church and hall and hear beautiful Bach cantatas and Monteverdi madrigals, we stand in front of them performing, yes, but also stewing on the terrible things that were just said to us. It’s a difficult juxtaposition of doing what we love, all the while questioning our worth and belonging. Nigra Sum was written to strip that away. The listener will hear the same pleasing beautiful tones and harmonies, but the veil is lifted beyond that. Instead of the words of long dead European poets and writers, listeners are confronted with what may be their own words reflected back to them. Performer and listener are now joined together in hearing the thoughts of the offended laid bare. I think it will be cathartic for some, and painful for others. But the intent is that everyone leaves that piece on the same page, regardless of race or life experience. At least that’s the plan! Weaved into this text is also the Latin text of a passage from Song of Solomon: Nigra sum sed formosa, or I am Black but beautiful. This has been set MANY times, and often with the word “sed” (but) changed to “et” (and). The rationale is that it gives agency to the speaker. A confidence and self-awareness that is fair and equitable. However, I love the original word “sed”, because to me it actually speaks to a strength and resilience that is so much more powerful to me. It’s more of a protest. It kind of says, “I understand that I do not register as beautiful under this society’s standards of beauty, but nevertheless, here I am. I am STILL beautiful. Whether you see it or not.” I love it, and it ties so well into the piece and gives a focus to the pain of these micro-aggressions. It further suggests, despite all of what is said to us and how it makes us feel, we will remain. We belong because we exist. The celebration of that resolve is what informs the rest of the programming in the concert. BIBA : Can you discuss some moments of micro-agressions that may inform your interpretation of the new work for this concert? RM : Heavens there are so many. A lot of them literally rest in the text of the piece. But I will share one story that doesn’t appear in the piece. A few years ago, in a city that I won’t say is Boston, I was at a church for a rehearsal. I happened to be early, and was standing outside of the locked room where we were performing, minding my own business, waiting for others to show. Before anyone arrived, an elderly white woman happened along my path. She looks at me, stops, smiles, and says, “Good morning, young man! How are you today? It’s good to see you.” I of course cheerfully respond. (A good Southerner would never pass up the opportunity to engage in this sort of unsolicited friendly engagement in a place like this.) Well, after a few moments of idle talk, just as I was expecting the encounter to end as pleasantly as it began, it all shifted. She went on past the niceties to ask, “It seems that I left my handbag in the parish hall. Would you mind unlocking the door for me?” Oh… she absolutely thinks I’m the sexton! I’d seen him earlier, and he was a Black guy for sure, but that was where the similarities ended. So I told her to head on over, and I’d grab my keys and meet her there. After she left, I stayed where I was and waited for the rehearsal to start. She might still be there! But it’s things like that which people of color in the arts (and more) deal with on a near constant basis. We laugh it off, and make light, but it’s more out of necessity and preservation. Truthfully, our lives would be just as good, if not better, if this were not our existence. BIBA : You are a frequent traveler. What have been some of the most inspiring places you have seen, and how have those trips helped you as an artist? RM : Too frequent. I’m writing this in my hotel room in Mexico City. I was in Vienna yesterday, and will be in Los Angeles in two days. Then Poland, then finally back to Boston to prepare for this concert. Inspiring places are too many to name. How do you choose between places like London, Leipzig, Malta, and Morocco? Everywhere I go is my favorite place ever (with a few notable exceptions), and there’s always something new and great to discover. And there are always new and interesting people who all have their reasons for being there. And it doesn’t take long for me to marvel at that. That these people from all walks of life, in every corner of the globe, completely separated by languages, customs, and experiences, are all united by music. The French see the same concert as the Italians. They hear the same music, and are typically moved in the same way. They all… we all have this same response to music. It’s music that preserves the feelings and emotions of people from different eras, and encases it in this ethereal amber that allows us to access and connect to it. Music is time travel. It’s everyday practical magic. And it’s ours. And this goes beyond Western styles and forms. All musics serve the same purposes, regardless of everything else. Traveling as much as I do, and seeing it proved over and over is what inspires me. It’s what fuels me. If attending the upcoming Castle of our Skins collaborative project with Handel + Haydn, please refer to the information above for the details! For more information about Reggie, please visit his website at: https://www.reginaldmobley.com ; and follow him on Facebook and Twitter!

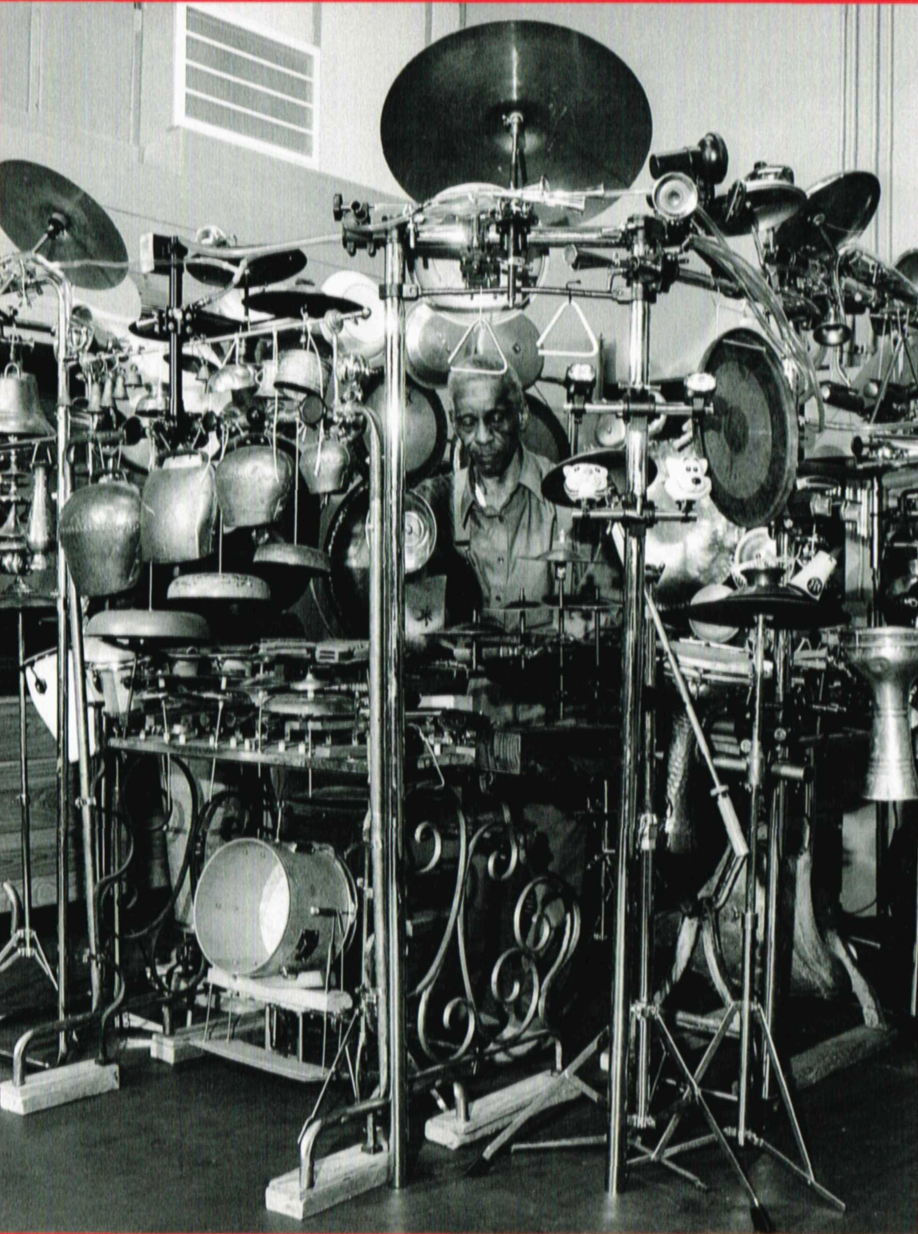

Posthumanistic Organology: Problematizing common organological taxonomies by way of the AACM and the heterogeneous sound ideal by Jessie Cox The term Organology is defined as “the science of musical instruments including their classification and development throughout history and cultures as well as the technical study of how they produce sound”[1]. The difficulty of taxonomizing instruments becomes evident when one considers the cultural aspects of any form of grouping as Kartomi suggests in regards to instrument classification by using the idea of “culture-emerging” and “observer-imposed” taxonomical systems. Work by Georgina Born on IRCAM for example, has shown how the organization’s aesthetic values imbued their technology and vice versa. Or, Kassler who alludes to the fact that new research in acoustics should change our system of instrument classification, which shows organology’s socio-historical and epistemological situatedness. Different apparatuses (or instruments) will give rise to different concepts and vice-versa – grouping things in a certain fashion will also create certain intra-actions (concepts, apparatuses, interactions, subjects, objects, etc.). Intra-action, a term used by Barad, is a term describing the interdependence and co-emergence of material, tools, concepts, subjects and objects (etc.); and can be used to describe the intrinsic relationship between instrument, player and conceptualization of the aural/physical experience. The affordances, and “idiomaticities” of instruments consequentially “reflect both the interface’s possibilities and the player’s motor habits.”[7] as well as an (onto-) epistemology. By way of Olly Wilson’s theorizing of African/African-diasporic musical aesthetics, the multi-instrumental practice of the AACM can be read as a problematizing of the more common western taxonomies of organology. In theorizing the importance of “the heterogeneous sound ideal” for African and African-diasporic art, he critically challenges organological taxonomies, such as the Hornbostel-Sachs system, and emphasizes the possibility of a different listening, music making, instrumental taxonomizing – musical structuring. The heterogeneous sound ideal manifests itself in two main ways. Firstly, by use of many “different” timbres as part of the same sonic texture (as opposed to homogenous textures such as a string quartet); and secondly, by utilizing “…a wide range of timbres within a single line”[8]. The AACM’s use of many variegated small instruments, and multi-instrumentalist approach to musical performance, is an epitome for “the heterogeneous sound ideal” and the ramification organology has on musical aesthetics. The practice of utilizing a variety of “little instruments” was introduced to the AACM by Malachi Favors, who was an autodidact in Afrocentric concepts and practices[4]. In particular the Art Ensemble of Chicago is known for its use of a multitude of instrumental colors. Theorists and critics have referenced this practice as a focus on “sounds as such”[10], “percussion instruments”[4], “small percussion instruments”[10], multi instrumentalism, etc. These readings of the practice re-sound/resonate an aesthetical understanding imbued with a certain 18th/19th century “European” (founded on the Praetorious’ work De Organographia) organological intra-action (For example a certain understanding of sound (“sound as such”), which has been described by Thompson as being “a racialized perceptual standpoint”[13] that seems to have possible relations with discussions of “culture-emerging” versus “observer-imposed” organological systems[2], where observer-imposed seems to be a similarly universalized position based on a theorizing of musical spectra as a fundamental taxonomizer.) and its connotations - including aesthetic values; whereas Braxton also uses another term to describe the “little instruments”: “sound tools”, or George Lewis who calls them “individual sound stations”, both avoiding the term instrument altogether [11][12]. If we consider this performance practice from the perspective of “the heterogeneous sound ideal” then we also have to change our conception of the musical instrument(s); since a grouping of instruments that focuses on, for example, the instrument’s material or its spectral component will favor a grouping (non-musical as well as musical) of “same-sounding” instruments (“instrumental families” – e.g string instruments sound “harmonious” together). This type of organological taxonomy will facilitate mainly (what is seen in western musical aesthetics as) homogeneous sound ideals. In light of this type of intra-action (structuring of instruments, music and even performer/listener) African aesthetic values are seen as having “unusual timbral combinations”[9]. If a different type of instrumental grouping principle is at work then the notion of homogeneity/heterogeneity changes its meaning and (“aural”) manifestation. The AACM, in particular the Art Ensemble of Chicago’s work, seems more in line with the heterogeneous sound ideal, and their use of many little instruments/multi-instrumentalism has to be seen in view of a different organological system. When it comes to the AACM, instruments might lend themselves better to an instrument classification based on the performers themselves and their respective instrumental practices – a grouping based around individuals (also posing questions concerning instrumental and human bodies). George Lewis thinks of the instrumental stations as assemblages, which would support the idea of a grouping of instruments (performers, musical material, and more) based around “closed systems” interacting with each other [12] – completely circumventing any of the “traditional” instrumental taxonomies. As Roscoe Mitchell mentions while discussing his two compositions “The Maze” and “L-R-G”: “…putting together the piece according to the instruments that each person was dealing with.”[14]. Thinking about instruments in this way changes the resultant instrumental combinations as well as the musical material and so creates another type of aesthetic than thinking of instruments as, for instance, instrumental-families. This reworking of fundamental conceptions of instruments, and with it, of all their connotations (musical parameters/concepts, socio-historical situatedness, semantics, etc.), completely changes the importance of such a, for musical aesthetics, seemingly peripheral field as organology. If one considers the different intra-actions of instruments/performers/music and their “onto-epistemological” positions, then organology becomes an increasingly important field for music, as well as for cultural and aesthetical theorizing. The example of heterogeneous versus homogeneous sound ideals, which are inherently linked to classifications of instruments, shows the aesthetical ramifications of taxonomies in music. Bibliography

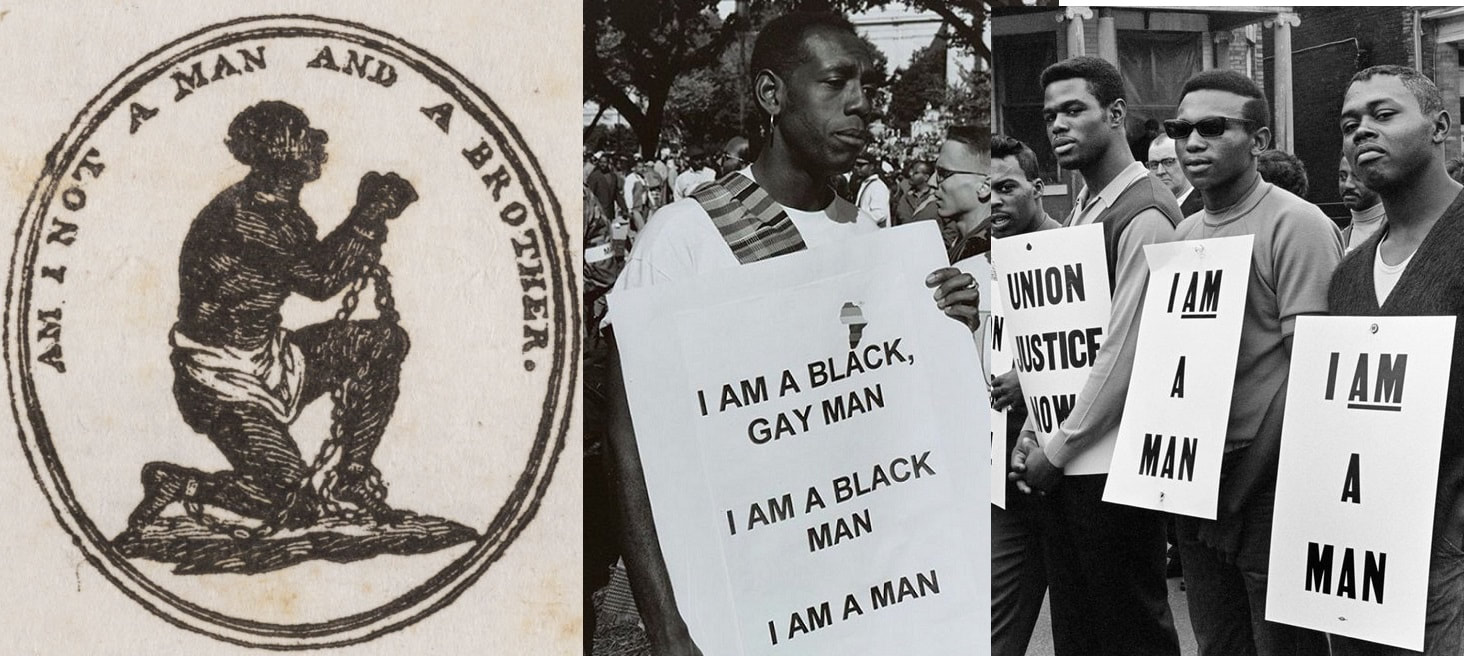

[1] http://dictionary.onmusic.org/terms/2442-organology [2] Kartomi, Margaret (2001). The Classification of Musical Instruments: Changing Trends in Research from the Late Nineteenth Century, with Special Reference to the 1990’s. Ethnomusicology, Vol. 45, No. 2, pp 283-314. [3] Born, Georgina (1995). Rationalizing Culture: IRCAM, Boulez, and the Institutionalization of the Musical Avant-Garde. University of California Press. [4] Kassler, Jamie (1995). Inner Music: Hobbes, Hooke and North on Internal Character. London, Athlone Madison/Teaneck: Fairleigh Dichinson University Press. [5] Barad, Karen (2007). Meeting the Universe Halfway: Quantum Physics and the Entanglement of Matter and Meaning. Duke University Press. [6] Radano, Ronald M. (1992). Jazzin’ the Classics: The AACM’s Challenge to Mainstream Aesthetics. Black Music Research Journal, Vol. 12, No. 1, pp 79-95. [7] De Souza, Jonathan (2017). Music at Hand: Instrument, Bodies and Cognition. Oxford University Press. [8] Wilson, Olly (1992). The Heterogeneous Sound Ideal in African-American Music. New Perspectives on Music: Essays in Honor of Eileen Southern. Detroit Monographs in Musicology/Studies in Music, No. 18. Harmonie Park Press. [9] Avorgbedor, Daniel (1999). Voiced Noise: The “heterogeneous sound ideal” as preferred acoustic environment in selective sub-Saharan African instruments and ensembles. The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America 106, 2169. [10] Steinbeck, Paul (2017). Message to Our Folks: The Art Ensemble of Chicago. The University of Chicago Press. [11] Braxton, Anthony (1985). Tri-Axium Writings. Vol. 1, Writings One. Frog Peak Music. [12] Lewis, George (2015). Expressive Awesomeness: New Music and Art in Chicago, 1965-1975. The Freedom Principles: Experiments in Art and Music, 1965 to Now. Chicago and London: Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago, in association with the University of Chicago Press. [13] Thompson, Marie (2017). Whiteness and the Ontological Turn in Sound Studies. Parallax, 23:3, 266-282. [14] Gross, Jason (1998). Roscoe Mitchell Interview. Perfect Sound Forever Online Music Magazine. (http://www.furious.com/perfect/roscoemitchell.html) [14] Restle, Conny (2008). Organology: The study of musical instruments in the 17th century. trans. Daniel Hendrickson, in Instruments in Art and Science: On the Architectonics of Cultural Boundaries in the 17th Century, ed. Helmar Schramm, Ludger Schwarte, and Jan Lazardzig (Berlin: Walter de Gruyter, 2008), 257-68. by Anthony R. Green In June, Castle of our Skins is gearing up to present its first ever multi-event project entitled I AM A MAN 2019. As a response to last year's successful Ain't I a Woman project, I AM A MAN 2019 is centered on Black masculinty, civil rights, and - of course - music. The week-long residency at Hibernian Hall will include community events with children, youth, and adults, educational discussions, a free screening of the bold Raoul Peck documentary I Am Not Your Negro, and two concerts that feature Black male performers (music and dance) and music by Black male composers - along with performers and composers who are not Black and/or male. This project is an inspiration from this famous civil rights declaration, which stems back to the 1700's. During the times of the transatlantic slave trade, grown men were often referred to as boy as a racist insult. As abolitionist movements strengthened, the catch phrase "Am I not a man and a brother?" arose as counter to such an insult, but also as a way to affirm the humanity of Black people. The emblem that was created in 1787 (left in the photo above) ultimately became a fashion statement promoting justice, humanity, and freedom. Almost 100 years later, the Ponca chief Standing Bear, in a court trial in Omaha to allow his son to be buried in Nebraska, declared in his plea: "That hand is not the color of yours, but if I pierce it, I shall feel pain. If you pierce your hand, you also feel pain. The blood that will flow from mine will be the same color as yours. I am a man. God made us both."

The declaration was used heavily in the 1968 Mephis Sanitation Strike. Five years earlier, Dr. Martin Luther King gave his iconic I Have a Dream speech at the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom (which was organized by Bayard Rustin). While that march was a momentous event, it did not rid Memphis from its heavily racist society, which equated to miserable working conditions for its Black workers, especially the sanitation workers. A year after that march, two sanitation workers died from being crushed to death by a garbage compactor in Memphis. While the workers wanted to strike after these deaths, the conditions were not amenable. However, four years after that (in 1968), two more workers died in the same way. Soon after these deaths - on February 12th, over 1,300 workers did not show up to work one day, and more left work as word got out. This action grew to a full-fledged strike of sanitation and sewage workers, as well as other sympathizers. As the racist mayor refused to meet with the workers or discuss their demands, the strike grew, attracting thousands of people, and visits from known activists and civil rights leaders. Trash started to pile up on the streets and violence broke out. Dr. Martin Luther King visited the striking workers in March and in April. His assassination on April 4th happened the day after he gave his last speech, commonly referred to as "I've been to the mountaintop." His assassination intensified the strike, which ended April 16th. All the while, many of the striking workers and marchers held signs that declared I AM A MAN! (right in the photo above) Outside of these events, this declaration has been used in many other marches and events, including pride marches (middle in photo above), festivals, poetry, songs, spoken word artistry, and more. It is powerful, simple, clear, and true; it is a message that must be taken seriously by ALL! Stay tuned for I AM A MAN 2019, first week of June 2019! |

Details

Writings, musings, photos, links, and videos about Black Artistry of ALL varieties!

Feel free to drop a comment or suggestion for posts! Archives

May 2024

|

Member Login

Black concert series and educational programs in Boston and beyond

RSS Feed

RSS Feed