|

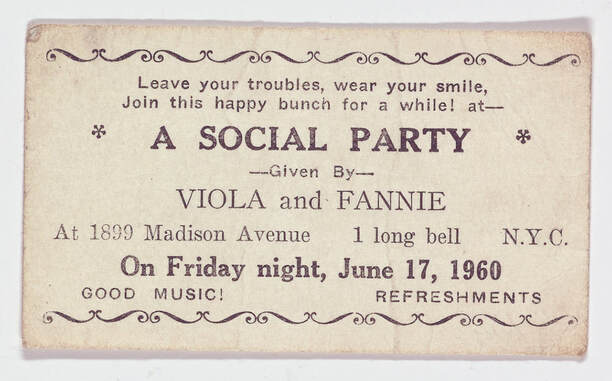

When I was named this year’s Shirley Graham Du Bois Creative-in-Residence, I thought seriously about how I could bring my creative work as a poet together with my research in African American literature and culture. Thankfully, it has been a very organic pairing as I’ve spent the last almost six years researching and archiving on the house-rent party tradition of the Harlem Renaissance in the 1920s. In 2017, I began a deep dive into rent parties after coming across a Slate article on Twitter about Langston Hughes’ collection of rent party invitations, which are a part of his papers in the special collections at Yale’s Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscripts Library. I was amused by the cheeky, rhyming phrases on the cards like, “Hop Mr. Bunny, Skip Mr. Bear, / If you don’t dig this party you ain’t no where!” When I eventually got to the Beinecke to see the collection for myself, I discovered that it is large. The invitations, which for the most part are the size of business cards, have dates printed on them from 1927 to 1960. Hughes was an archivist, and he realized the cultural import of the rent party phenomenon so much that he saved a ton of invites in his papers. For his meticulous archival practice, I am grateful. House-rent parties, also called social whist parties, breakdowns, struggles, and a host of other colloquial names, were the turn-of-the-century iteration of southern jook joints and church socials. In the south, black people created spaces for dance, music, enjoyment, and pooling their resources when they had leisure time from their sharecropping labor. When black people migrated en masse from the south to the industrial north during the Great Migration of the early 20th century, they took with them the jook joint and church social ways of knowing. They were faced with a housing crisis in New York specifically: limited housing options, dilapidated buildings, and disproportionately low wages and high rents compared to white families. And so the rent party—hosting people in one’s apartment and providing music, southern food, and good vibes for a small cover charge—became not just a means to an end but a way of continuously cultivating joy and centering pleasure in a time of serious economic, social, racial, and environmental disparities. Rent parties were so ubiquitous and so much a part of the fabric of 1920s Harlem because they were semiprivate and semipublic, they were safe spaces for nonbinary and nonheteronormative gender and sexual expression, and they were the places where jazz music had its origins alongside numbers running and other “underground economies,” as LaShawn Harris terms them.

Langston Hughes’ extensive collection of rent party invitations gives insight into just how longstanding a tradition rent parties are. Katrina Hazzard-Gordon says that, like many things still present in our culture, rent parties can be traced back to plantations of the antebellum south where enslaved people were resigned to organizing covert recreational and social gatherings from church services to celebrations to avoid the watchful eyes of their masters and overseers. Hazzard-Gordon argues that this secrecy, or at least the practice of gathering without white presence or control, carried over into the post-Reconstruction period. My fascination with this understudied tradition of rent parties and community economics comes from both the insistence on black joy that they represent and the longevity of their presence in the real world and in media. In the 2002 quadrilogy film Friday After Next starring rapper Ice Cube, he and his cousin throw a Christmas rent party to avoid being evicted after their apartment is burglarized and their rent money stolen. In season two of the Hulu original series Woke, character Ayana throws a 1920s-inspired rent party to save her indie magazine’s office, which has been doubling as her apartment while she’s low on cash. There are numerous other popular culture remnants of the original rent party tradition. And there are black communities, like The Salt Eaters Book Shop (aptly named after Black Feminist author Toni Cade Bambara’s powerful novel) and its followers in Inglewood, California, who recently hosted a Beyoncé RENAISSANCE-themed rent party that went over so well, they’ve come back with a Sade-themed party and have plans to keep the gatherings going. The rent party’s legacy continues to uphold and uplift black folks over 100 years later, and I see it as a model for how we might all approach community care, subsistence, and joy. This is all to say that I’ve truly fallen in love with the history and culture of rent parties the more I have researched and learned about them. Black people’s innovative ways of being in a very antiblack world never cease to amaze and inspire me. We have working-class black folks of the Great Migration to thank for what we now know as jazz, and how beautiful is that? People working the most backbreaking and low-paying jobs as domestics, shoe shiners, and porters found the strength and energy to create the spaces that allowed improvisation and musical genius to flourish. Their contributions of living and being changed the world, and my hope is that the research I do and the upcoming Harlem Renaissance (and yes, rent party!) collaborations I am curating with Castle of Our Skins will honor these brilliant people and carry on their spirit of togetherness and uninhibited enjoyment. -Angel C. Dye

0 Comments

|

Details

Writings, musings, photos, links, and videos about Black Artistry of ALL varieties!

Feel free to drop a comment or suggestion for posts! Archives

May 2024

|

Member Login

Black concert series and educational programs in Boston and beyond

RSS Feed

RSS Feed