|

‘Virtuoso’ is the Language of Great Musicians; ‘Black’ is not His Name Part III: WeWrite to Rewrite & Re-right History by Kristen Adams When classical music began trending among higher classes, the arts community welcomed the new music sector. While music is a powerful force in bringing community together, it further distanced elites (who added classical music and composers to their required “cultured” discourse) from commoners (unable to access the sphere). Classical music was not solely a topic of conversation between the elite audience. It provoked a wordless conversation amongst the composer, performer, and listener whose language traversed temporal, physical, political, and psychological boundaries defining the elite culture. One writer writes notes, there are two distinct ways of attending to sound: one that focuses on the thereness of the sound, on the sound-producer; and one that focuses on the hereness of the sound, on the physiological and psychological effects of sound on the listener”. With 2020 still feeling fresh, we start the decade building upon the foundations of excellence, creativity, and passion that Black composers before us also embraced. Their lives show a different story of a Black man during slavery, and their achievements demonstrate how a community can be enhanced in the absence of racial exclusion. In a society that created a label, “African-American music” to define our creativity as the beautiful Blues, R&B, Caribbean, Afro-beats and Rap styles, the reality is that there is no limit to music Black people create. Joseph Bologne, Chevalier de Saint-Georges was not the only violinist whose legacy is clouded by the shadow of a white counterpart. George Augustus Polgreen Bridgetower was a virtuoso whose birth is estimated to have been on February 29, 1780 from a Polish mother and Caribbean father. He had a younger brother, Fredrick, who was also a very talented cellist. During George Bridgetower’s time, he was considered “the African Prince”. While characterizing African with prince is a positive representation of the often misrepresented continent and its people, it was an exoticization of his talent and ethnicity, given that he was born in Poland and was not recorded to have had any ties to a kingdom. However, this does speak to notions of identity that seem foreign to North America but innate in Europe and other parts of the world: nationality by blood, an increasingly disputed reality for its political and human rights ramifications. Bridgetower made his professional debut at the Concert Spirituel (one of the first public concert series in Europe) in Paris in April 1789 at the young age of nine years old, when he played a violin concerto by Giovanni Giornovichi. Despite his early start of exceptionalism, his accomplishments are more difficult to find in writings. Instead, the paper trail of his legacy is dominated by his fall from grace with Ludwig van Beethoven. Considering him a good friend and talented virtuoso, Beethoven dedicated his Sonata for Violin and Piano No. 9 in A Major, Op. 47 to Bridgetower, inscribing the following (translated): Mulatto sonata composed for the mulatto Bridgetower, great fool and mulatto composer’. They performed its debut together in Vienna in 1803. However, after a dispute, Beethoven decided to dedicate the piece to Rodolphe Kreutzer, a man he never met whose own response to this parallels the rewards so easily granted to white men with less credentials than their highly accomplished POC counterparts. Though we all call it the Kreutzer Sonata, Kreutzer never played the piece, saying that Beethoven did not understand how the violin worked, making the piece unplayable. If you listen to the sonata, you may notice how the harmonies hold the tensions, intensity, command, determination, righteousness, shiftiness, emotional vigor and dialogue between the violin and piano that colored the end of their friendship and Beethoven’s decision to alter his dedication. While this truth is fascinating, Bridgetower’s life is more than this phase. Bridgetower was a violinist and composer who was considered a “child prodigy, a crown favorite, a master violinist, and a respected teacher”. After one of his performances, a newspaper circulating during his time remarked, “[George Bridgetower] had a more crowded and splendid concert on Sunday morning than has ever been known in this place. There were upwards of 550 persons present, and they were gratified by such skills on the violin as created general astonishment, as well as pleasure from the boy wonder. The father was in the gallery, and so affected by the applause bestowed on his son, that tears of pleasure and gratitude flowed in profusion." His father attended many of his performances and supported him when they traveled to Windsor to begin what would be a lifelong tour around Europe when Bridgetower decided to make a living performing. While he was elected to the Royal Society of Musicians on October 4, 1807, he also earned a Bachelors of Music from Trinity Hall in 1811. He would also hold the position of concert master in the Prince of Wales’s private orchestra for 14 years. Bridgetower is not recorded to have had tense relations with his contemporaries, but was welcomed and enjoyed friends and mutual mentorships. Several of his compositions have survived over the passing time, but very few are recorded. For those wanting to read more about Bridgetower, Rita Dove wrote a book about him entitled Sonata Mullatica; A Life in Five Movements and a Short Play. Both Joseph Bologne, Chevalier de Saint-Georges and George Augustus Polgreen Bridgetower created lives that gave them meaning, followed their passions, and integrated spaces that some may believe are just starting to be integrated in the 21st century. Their stories inspire and push us to demand more recognition and inclusivity in the classical world as we ask you to embrace your own passions.

What gives your life meaning? How will you make an impact? We love music because we love its sound, we love its feeling, we love its inventiveness, and commend those who dare to break the silence. We are all creators of our lives and of history. ‘Virtuoso’ is the language of great musicians. You hold the key to your greatness. “We die. That may be the meaning of life. But we do language. That may be the measure of our lives.” – Toni Morrison

2 Comments

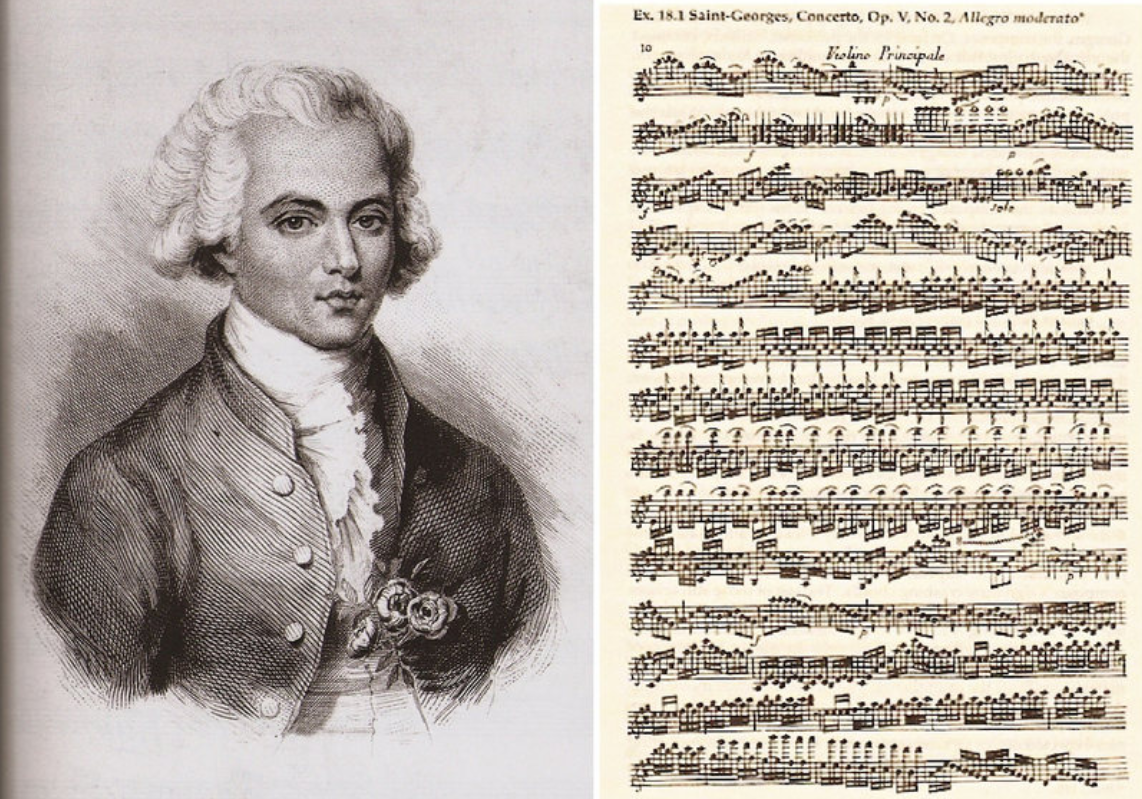

‘Virtuoso’ is the Language of Great Musicians; ‘Black’ is Not Their Name Part II: Lift Every Voice by Kristen Adams “Our lives begin to end the day we become silent about things that matter.” – Dr. MLK, Jr. On the third Monday of January annually, the United States remembers Reverend Doctor Martin Luther King, Jr. (MLK) for his persistence and his achievements in his vast activism: the Civil Rights Movement, Voting Rights Act, declarations of peaceful protest in Letter from a Birmingham Jail, Anti-Vietnam War advocacy, March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, the Poor People’s Campaign for economic change, and the beginnings of his endeavor to unite with Malcolm X. While we honor his memory, we hear his words and those of others who continue to open many doors. “Everything will change. The question is growing up or decaying.” – Nikki Giovanni Hopefully those reading this have enjoyed listening to some compositions of Joseph Bologne, Chevalier de Saint-Georges after reading Part I, and are ready to consider the part of his journey that resembles the experiences of Black activists from the 18th century to the 21st. To conclude this call to “say their names”, next week we will discuss George Bridgewater (another ‘virtuoso’ overshadowed by a white European counterpart), and encourage you to uncover other Black women, men, and people in all sectors whose memories are clouded by white supremacist erasure. “Black people, we are fully deserving of the room and space to fully express our humanity.” – Opal Tometi If there is anything we learn in Black skin, it is to persist, it is to activate, it is to be. Bologne’s life, beginning in Guadalupe from Senegalese, French, and Italian ancestry, was a journey that accepted no limits. Among his known works, which include three sets of string quartets, two symphonies, eight symphonie-concertantes, six operas comiques, three violin sonatas, 14 violin concertos, a sonata for harp and flute, a bassoon concerto, a clarinet concerto, a cello concerto, and six violin duos, only few can still be found. “Music makes us want to live.” – Mary J. Blige While it may not come as a surprise to the Black community - accustomed to its work, people, culture, and creations stolen so often - one of Bologne's compositions exists in his contemporary’s piece, and so it is most likely to have been heard in the context of a different musical story. Take a guess … a composer whose unrequited competition was mentioned in Part I … Mozart. As Andrea Valentino quotes Chi-Chi Nwanoku in this article, “It is no accident—and tells us a lot—that Mozart copied note-for-note from a Bologne violin concerto into one of his own [pieces].” “The brutal history of colonialism is one in which white people literally stole land and people for their own gain and material wealth.” - Patrisse Cullors Mozart not only felt threatened by Bologne’s excellent work but was so insecure in himself that he stole a gesture from Bologne’s symphony-concertante for two violins. Yet he is somehow the one whose memory shines through history and continues to be played by all major orchestras. “It is not who you attend schools with, but who controls the school you attend.” – Nikki Giovanni Bologne’s legacy of musical works was not subdued by this theft, but rather by the society that saw only his Blackness, despite his great musical, political, and military accomplishments. Before his 20th birthday, Bologne received numerous dedications from musicians. Two prominent musicians, Antonio Lolli and François-Joseph Gossec, dedicated two Violin Concertos Op. 9 and Six Trios Op. 9, respectively, to Bologne. His public debut, soloing with the Concert des Amateurs in 1772 and performing his two Violin Concertos, Op.2, “received the most rapturous applause”, according to Mercure de France. While Bologne’s talent is just one of the many accomplishments we remember, the complexity of his works was used as an excuse to devalue them. Nevertheless, we do not let those excuses govern our perception. “Definitions belong to the definers, not the defined.” – Toni Morrison The Paris Opera refused to listen to his command because they would not be conducted by a Black person. When he was going to be named Artistic Director of the Royal Academy at the Opera, two female leads protested so extensively against working with a “mulatto” that they did not instate him. “Never limit yourself because of others’ limited imagination; never limit others because of your own limited imagination.” – Dr. Mae Jemison In his political life, his clear commitment to and successes for the French Revolution were still questioned by authorities, landing him in prison for one year due to suspicions of his true allegiance. Even this did not stop him from working to create a better world, be it through music, military defense success, or human rights abolition activism. “He who is not courageous enough to take risks will accomplish nothing in life.” – Muhammad Ali As hinted prior, Bologne was already “falling out of fashion” due to the complex music he could create and the society that was ready to discard him with the slightest misstep. Yet, he disregarded those risks and advocated for Black rights and abolition, initiating Black political activism in Europe. His human rights stances, considered political only in oppressive societies, reveal the nuances of a society that loves a prodigy but hates a certain skin color. “Teach her to reject like-ability. Her job is to be her full self … honest and aware of the equal humanity of other people.” – Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie His activism recognized and utilized his own privileges, gained from a father who allowed him to take his last name, despite the norm to disown children considered illegitimate. Despite his education, in which he excelled, and his accomplishments and dedication to the queen and to his country, he was still not considered a legitimate person, and therefore enjoyed no rights of citizenship. Yet Bologne continued to color his life with great endeavors, as if he never heeded these moments as setbacks, just re-directions. “You may not control all the events that happen to you, but you can decide not to be reduced by them.” – Maya Angelou After all the doors he opened and spaces he enhanced, he continued pushing more boundaries and embracing his passions. He encourages us to consider our own impact in the world. How is one to be a creator of music, using sound and harmonies to break the stagnant air, and then be silent and void of this intensity in the face of injustice? “I had spent many years pursuing excellence, because that is what classical music is all about ... Now it was dedicated to freedom, and that was far more important.” – Nina Simone While some mark his dedication to equal rights as the end of his social success, it was the beginning of a passionate struggle against racism in Europe and in the world that continues today. When he died in 1799, newspapers tried to control his impact by writing about his musical self and completely ignoring his political contributions to both France and to Black people’s rights. Nevertheless, he succeeded in cracking the comfort for which his society yearned in dehumanizing other races, opening yet another path toward revolution.

“Whites and Blacks should be taught to respect their fellow human beings as an integral part of being educated.” – Mamie Phipps Clark While our fight continues worldwide, so does recognition of Joseph Bologne, Chevalier de Saint-Georges. One such recognition gives listeners the opportunity to listen to his music live. Artistic director Marlon Daniel coordinates the Festival International de Musique Saint-Georges held in Guadalupe, so that his memory and music live on. For our international readers, we thank you for standing in solidarity with the Black American community, for we rise together. “I used to want the words ‘She tried’ on my tombstone. Now I want ‘She did it.’” – Katherine Dunham “Be a bush if you can't be a tree. If you can't be a highway, just be a trail. If you can't be a sun, be a star. For it isn't by size that you win or fail. Be the best of whatever you are.” – Reverend Doctor Martin Luther King, Jr. Listen to the Black National Anthem ‘Virtuoso’ is the Language of Great Musicians; ‘Black’ is not His Name: Part I by Kristen Adams Some of the greatest musicians saw a virtuoso for their talent, not their race (after its invention). The innate nature of music and true artistry is to break the boundary between what the viewer knows and how this knowledge, belief, emotion, or controversy is perceived. The classical world has had individuals stretching musical, political, and physical boundaries for centuries, and listeners are excited to enjoy each new creation. In recognizing the virtuoso/a as a musician with tremendous skill, rather than aligning it with its root, virtu’, that was used to describe masculine noble men, the community opened the language to be inclusive so that the classical realm could be too. When language accepts, so does society, no matter how minute or expansive. It is up to us, who remember, to keep the language we speak as open as the music our souls and instruments create. Therefore, we’d like to consider a musician whose life and musical achievements resemble the Black boy joy we recognize today: Joseph Bologne, Chevalier de Saint-Georges (1745 - 1799). During his life, he mastered his crafts and broke societal boundaries in different ways, yet he still became remembered in the shadow of a white classical composer. Today, we change that, and we continue the legacy of the Black Lives Matter Movement that cries “Say his name”. Joseph Bologne, Chevalier de Saint-Georges, is known as the “Black Mozart”, but if history measured his skill and impact, Mozart would have been known as the “White Bologne”. Sounds off, right? Better to remember Joseph Bologne, Chevalier de Saint-Georges, and Mozart. We can delve deeper to help the name stick, if needed. “Black Mozart” was used to refer to Joseph Bologne, Chevalier de Saint-Georges because Mozart was so inspired by Bologne’s talent and artistry that he was always competing against him and driving himself to be better than Bologne. Some would argue that Mozart’s opera The Magic Flute, reflected his sentiments towards Paris, and the character Monostatos was his depiction of Joseph Bologne, Chevalier de Saint-Georges, whom he considered his nemesis. However, Joseph Bologne, Chevalier de Saint-Georges is not remembered to have addressed this competition, and instead was living his best life being the local celebrity that he was. Bologne was not known solely in his nation, but was regarded around the world by major figures of his time for his virtuoso in composition and performance. Years later, with a different tune, we cry, “Say his name”. Joseph Bologne, Chevalier de Saint-Georges was a violinist, harpist, composer, colonel, and champion fencer who was also invited to many balls because of his dancing skills. Born from a Guadalupe plantation owner and an enslaved African, he was considered an illegitimate child, but that did not stop him from mastering his many crafts and breaking the stereotypes to be remembered in such high esteem. When Joseph Bologne, also known as “god of arms”, graduated from the Académie royale polytechnique des armes et de ‘l’équitation (fencing and horsemanship academy), he was made an officer of the king’s bodyguard, becoming Joseph Bologne, Chevalier de Saint-Georges. It is possible that you recognize his name if you were lucky to learn about the French Revolution through an unracialized, and thus authentic, lens. He not only volunteered to fight, but he also became colonel of the first Black regiment in Europe, a cavalry brigade of 1,000 volunteers of color, with whom he halted ‘The Treason of Dumouriez’. Even while he was volunteering, he gave weekly concerts; his passion for music transcended all boundaries and concepts of what a military experience should be and what his life could be.

He continued to create, and began writing operas, directing Marquise de Montesson’s prestigious musical theater, in addition to conducting Le Concert des Amateurs, which he transformed into one of the best orchestras in Europe during his lifetime. Amidst the high regards with which society viewed him, one that stands out is John Adams’s declaration that Joseph Bologne, Chevalier de Saint-Georges, was “the most accomplished man in Europe”. There are many rich and exciting aspects of his character and achievements. We invite you to explore his music, read more about his life, speak his name, and remember Joseph Bologne, Chevalier de Saint-Georges. Enjoy listening to his music this week! Stay tuned for part 2 next week. Here is a piece to start your exploration! Happy New Year from the Castle of our Skins team! COOS is now in the second half of its seventh season. Time sure does fly! In this second half, COOS is planning two projects that feature music by African composers. It has been incredible researching this music, connecting with composers and musicians, and expanding our musical vocabulary. Fitting then is this first BIBA Blog of the new year - an artist spotlight of the incredibly talented, young South African composer, Monthati Masebe! BIBA : How did you get your start in piano and in composition? Did they happen at the same time or one after the other?

MM : I come from a very artistic family lineage, both from my mother and father's side of the family. Ancestors I have never met before would speak to me in my dreams, teach me to play the mbila (also known as kalimba) or recite proverbs through song. I also always had toys that were mini pianos as a child, and at the age of 8 begged my mother to pay for piano lessons. I immersed myself in classical piano for 12 years and would always find myself making mistakes in my pieces and turning those mistakes into songs. I paid more attention to harmony and phrasing than precision and techniques. In 2016, I realized that I enjoyed the process of creating music and I would much rather create music for musicians to play. I believe very strongly in music cognition and that frequencies in sound can affect the frequencies in our brain. Composing music that can have an impact on how we feel, how we speak to ourselves internally, what we associate with emotions – that's how I make meaning of music. BIBA : Your musical voice includes many different styles, genres, and approaches. What draws you to these styles and how do you combine them in your compositions? MM : I come from a very diverse cultural background. I grew up in a home that was pan-Africanist in thought, food, art and spirituality. I listened to African indigenous vocalizations from all regions of Africa. Sometimes we would meditate with mbira music. My ability to identify African indigenous instruments led me to listening to genres that incorporate it. Latin jazz, cross-over jazz, afro-psychadelic rock, underground electro subgenres like electro-chaabi, kwaito, downtempo and lo-fi. I like to seek out what I'm drawn to about each genre and embody that in my orchestration or textural preference. Sometimes the sound of an instrument will be the inspiration for a certain synth sound or a percussive pattern will influence the rhythms I choose for instruments. I think there's a natural osmosis that happens between music and memory, but not everyone is as conscious of how we all seek out patterns of familiarity to define our musical taste, both for listening and for creating. BIBA : In your beautiful piece Disturbed Taboo (Dzata) for the Stockholm Sax Quartet, you explore complex rhythms and tonalities to evoke emotions associated with a violent, annual traditional practice. Can you please explain a bit more about this practice? What moved you to compose a piece about this practice? MM : Bare knuckle fighting (amongst other cultural practices performed by various tribes) is a practice that symbolises strength and pride. Musangwe is a the name of this tournament and it is said to be a therapeutic experience that puts individuals into a trance that makes the seemingly painful experience tremendously bearable. The grounds are prepared with traditional herbs and plants, as well as a ritual for the ancestors to protect fighters in the tournament. It happens annually from the 16th of December to the 1st of January. Only one person has died since the beginning of this practice in the early 1800s. I wrote about this piece with the intention to interrogate the grey areas in life which usually go unspoken. When we remove the veil of right or wrong, maybe we'll start to see beauty in the mystique or at least see how our lack of knowledge about certain ways of life can make us assume the worst of people and practices. I never really fit in, and because of that I always found myself being understanding about the unconventional. I feel like I can relate to being misunderstood. BIBA : Your artistic interests expand to visual art, including film and installation. In all of your endeavors, what is the most important aspect of yourself that you place in your various projects? MM : I think I always want time to be a concept that is considered. That time can be confusing and feel like it has no start or finish but just an infinite loop of sonic pictures. That repetition can be daunting but sometimes it can be exactly what one needs to feel safe in the chaos of life. This sounds a bit flowery and poetic but if you listen to my music you'll see the common thread if you think about time in those ways. I never intentionally wanted this to be the signature but for some reason it's all I ever think about musically. BIBA : I give you the commission of a lifetime - unlimited access to any musician, artist, studio, art supply, software/technology that you want, unlimited time, and your choice of location. What would you create?!? MM : I would make a 7 part series of a global residency that has people composing with material that is considered non-musical to make a statement about the global challenges we don't speak about enough. For instance, imagine an orchestra of car hooters all lined up and down hills all over the world, commenting on carbon emissions and the environmental crisis we are faced with. The cars will all be grafitti'd by artists and it will be live streamed and turned into a documentary series. I really think we should be saying more as artists. And residencies or commissions are a good way of getting impactful information out there. ----- To learn more about Ms. Masebe, you can follow her on Instagram @Monthati_M, and you can listen to some of her music on SoundCloud! |

Details

Writings, musings, photos, links, and videos about Black Artistry of ALL varieties!

Feel free to drop a comment or suggestion for posts! Archives

May 2024

|

Member Login

Black concert series and educational programs in Boston and beyond

RSS Feed

RSS Feed