|

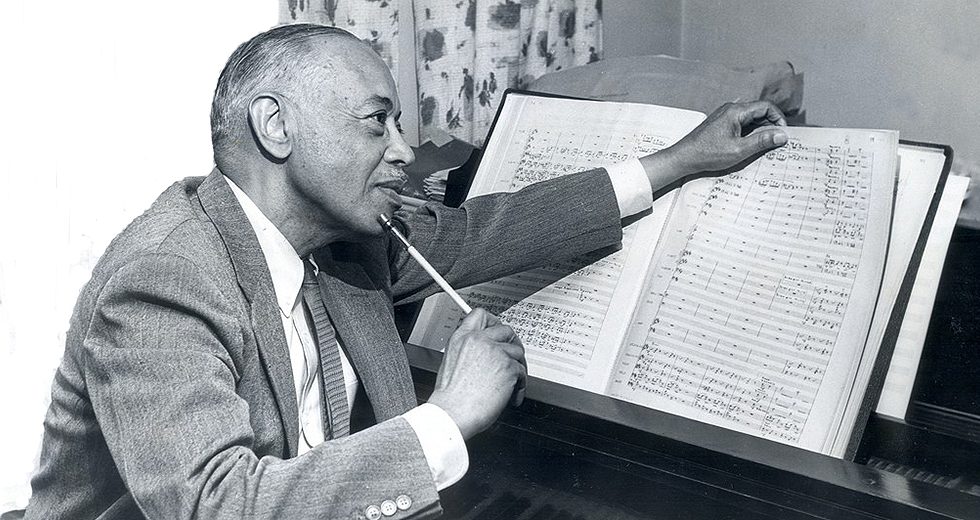

by Anthony R. Green This morning, walking down the street in Berlin, I saw an article in the Berliner Morgenpost about Beethoven and how the world is preparing for celebrations of his 250th anniversary. Wonderful! I am sure many are anticipating the articles, educational events, displays, and thousands of concerts all dedicated to Beethoven's life, perhaps some of his contemporaries and inspirations (such as Cherubini), and his music. I personally am anticipating catching a performance of the Grosse Fugue, which - in my opinion - is one of the most transcendental pieces ever composed. By now, you probably have noticed, like I did, that these big anniversary celebrations of the "great masters" are staged by institutions that have defined the composers who are considered the "great masters", and ... well ... many well-deserving composers have simply not made the cut, for ... various ... different reasons. With that, let's consider adding William Grant Still to next year's major celebrations. Born in 1895, 2020 will mark his 125th anniversary! With so many barries broken, so many accomplishments achieved successfully and gracefully, and such incredible music, Still deserves the title of "Great Master" as much as Beethoven. Still composed over 150 works, including 5 symphonies and eight operas! He was the first Black composer to have a symphony played by a major symphony orchestra, the first to have an opera played by a major opera company, the first to have an opera broadcast on television, and he was the first Black person to conduct a major symphony orchestra in the US. How did he achieve all of this? Talent, hard work, dedication, persistence, strength, tenacity, and so much more. But the mere fact that he was so prolific, often performed, sought after, and respected is a testament to his character and the worth of his music. So where are the Still celebration preparations? Have you noticed them? Have you noticed a lack of them? There is still time to write letters, posts, blogs, and make other requests to demand to hear the music of Still in celebration of his 125th next year! The concerts and celebrations unfortunately will not happen if people do not ask. Please ask! Demand! Don't forget about William Grant Still! In the meantime, listen to this beautiful recording of Summerland by the incomparable Althea Waites!

0 Comments

Happy Sunday BIBA and COOS fans! Castle of our Skins's next event is part of its upcoming residency with the Longy School of Music at Bard College in Cambridge, MA. From the 12th to the culminating concert on the 14th, Castle of our Skins will present a host of various events celebrating the life and music of Trevor Weston. For a complete list of the events, please click here! To learn more about Trevor Weston, his life, international career, and music, keep on reading! BIBA: You credit your start in music to the prestigious St. Thomas Choir school in NYC when you were only 10. Did you grow up in a musical household? How did this initial training lead to you becoming a composer?

TW: I grew up in a creative family that loved and respected the arts. My father was an interior designer and a graduate of Music and Art High School, now the LaGuardia School, and Pratt for College. My mother was the daughter of the best seamstress and sewing instructor in Speightstown, Barbados. My father’s brother was a fashion designer, graduate of FIT in NYC. Creating new unique works was a cultural imperative in my family. My brother, sister, and I could not have coloring books because we had to make our own pictures. At the same time, both of my parents loved music. During his teens, my father studied voice with William Lawrence, accompanist to Roland Hayes and Marian Anderson. I believe Lawrence was also a rehearsal pianist for the Boston Pops. In high school and college, I accompanied my father singing Harry T. Burleigh spiritual arrangements, most likely as a result of his voice lessons with William Lawrence, and arias by Bach and Handel in church. My mother was also very musical. Growing up in the Anglican church, my mother knew every hymn and psalm tune in that tradition. When my mother wanted to locate the three of her children in public places, she would whistle a major triad in second inversion. My mother was the first person to tell me that my repetitive little piano piece needed something called a bridge. Music was everything in my childhood. At the St. Thomas Choir School, I learned very quickly that music was not only enjoyable but an important and powerful form of human communication. The choir performed music by living composers together with a wide range of music from the renaissance to the twentieth century. The first piece I composed studying with TJ Anderson was based on a musical figure I wrote in response to the Kyrie from the Mass for Five Voices by Lennox Berkeley. I still remember hearing this piece as a 5th grader and being completely mesmerized by it. My experience at the Choir School expanded my knowledge of music as a powerful entity. Performing music well was not mere play, but an important contribution to the world. An important lesson I learned at the Choir School is that you may never know how your music will affect others so it is best to always try to say something important. BIBA: In your incredible and diverse career, you have spent some time in Paris. What were some of the ways Europe had an influence on your compositional voice, and how did your studies there differ from your studies in the United States? TW: I studied in Paris on an award from UC Berkeley, the George Ladd Prix de Paris. While in Paris, I attended courses in Music History Pedagogy at IRCAM (Institut de Recherche et Coordination Acoustique/Musique). This gave a better understanding of the French and by enlarge the European new music scene. I also attended numerous IRCAM concerts and heard composers who are rarely performed in the US. Most importantly, I felt like a valued and visible part of society in Paris as a composer. In a way, just living in Paris changed my identity as an artist. Although I mostly worked on my own, I did have a great lesson with Gérard Grisey. He listened to a few of my works and then asked me, “Do you know who you are as a composer?” He heard elements of Bartok, and generic modernism and he was not sure if I did this deliberately or by default due to my education. Paris forced me to not only consider my role as an artist in society but also forced me to reflect on what made my music unique. BIBA: The voice features prominently in your repertoire, having a substantial number of opera, solo and accompanied choir works, and solo vocal works/art song. What are some of the ways that text informs your musical decisions as you work with the voice in your works? TW: When I was a choirboy, I disliked singing psalms using Anglican chants because I thought they were boring, repetitive chanting with limited melodic content. It turns out that not only do I love them now but the relatively few pitches used to sing these chants increased my sensitivity to text expression. In many ways, the words are the music in Anglican Chant. As a result, I have to settle on the text before I start writing vocal music because the music always comes as a response to the text for me. I then arrange the text to create the necessary form for the work. There are certain words that speak to me musically and others that do not. I am not a fan of using wordy texts because I prefer to repeat words in different ways as a type of explication of the text. The words I choose usually have colorful sounds, sonorities or suggest vivid imagery. Some of my works for voice were inspired by the sound of one word as the focal point of the piece. BIBA: Your career also includes extensive amounts of research, having co-authored a piece about Duke Ellington with the late, great Olly Wilson, having edited Florence Price's Piano Concerto, having researched various topics and primary sources for your own compositions, and more. What were some of your favorite "discoveries" in your research and how have they influenced your musicality? TW: I told Olly Wilson that his writings on the “conceptual approaches” that link the creation of music in traditional West African Music and music by Black Americans were like the Rosetta Stone to me. They unlocked an understanding of how Music of the Diaspora works and why it is constructed in similar ways around the world. I composed a piece for organ, Arise, my Love, based on the clapping on beats two and four heard in traditional African American music. The syncopation creates a basic level of necessary rhythmic clash in the piece. Ellington definitely saw himself as part of a long lineage of musicians writing in a Black musical tradition. This fact became more apparent conducting research while working on the publication with Olly Wilson. I learned much from Florence Price. The final section of Florence Price’s Concerto in One Movement is a masterpiece. She combines Ragtime or African American 19th century dance rhythms and orchestral music in a truly interesting way. The last movement of my work Griot Legacies is directly influenced by Florence Price. I decided to conclude my work like Price with upbeat African American dance rhythms. BIBA: I give you the commission of a lifetime with unlimited funding, time, and access to whatever musical/performing forces you desire. What would you compose? TW: I would compose a large scale work that includes a whole town. An outdoor orchestra, large choir and possible church bells too. We rarely come together as communities anymore. It would be a huge statement that would include the audience singing along with familiar melodies accompanied by an orchestra, choirs and church bells. A piece of 1812 overture-like grandeur that reinforces community and identity. ----- Vist Trevor Weston's website here! Follow him on Instagram here! |

Details

Writings, musings, photos, links, and videos about Black Artistry of ALL varieties!

Feel free to drop a comment or suggestion for posts! Archives

May 2024

|

Member Login

Black concert series and educational programs in Boston and beyond

RSS Feed

RSS Feed