|

Happy Sunday BIBA readers! This week, BIBA is featuring another composer, who is taking the music world by storm! Born in 1996, Quinn Mason's laundry list of awards is impressive and enviable. As you will read in his interview, his repertoire list is also quite long, including at least 8 works for large ensembles, at least 5 string quartets, other chamber works, vocal works, and solo works. I look forward to hearing more about Mr. Mason as his career progresses. Until then, please learn about this fantastic young composer (if you do not know him already)! BIBA: What is your earliest musical memory and how did you come into the world of composition?

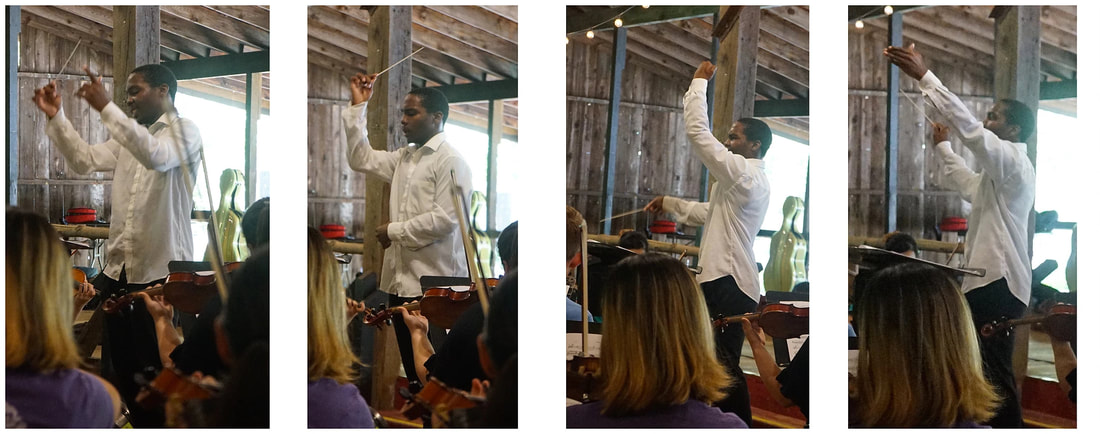

QM: I first came into contact with classical music at the age of 10 during an elementary school trip to the symphony. Before then, I had been listening to classical music via the radio and CDs but had never experienced it live. I still remember my very first live concert clearly: Prokofiev’s Peter and the Wolf performed by the Dallas Symphony Orchestra with Sting(!) narrating. I remember being completely overwhelmed by the different sounds the musical instruments were making and how their different timbres contributed to the telling of the story. It was very eye-opening and still sticks with me to this day. A couple of years later, I had started cello lessons for free as a scholarship student of a local non-profit organization, the Fine Arts Chamber Players. During my practice sessions, I would experiment with the etudes and add notes or take notes out. Eventually, I would try writing my own ‘etudes’ on staves I had drawn and would take them to my teacher who was nice enough to try and decipher my handwriting and play what I had written. Hearing something I had created out of nothing was an indescribable experience. I wanted to do more and better than I did with the etude, so I eventually acquired numerous scores and recordings, which I delved into with insatiable curiosity. I mostly listened to orchestral music in my early music training, which is why I have a particular interest in writing orchestral music. I remember being addicted to the piano and was often the last one to leave piano class because I kept experimenting with the sounds of the digital piano (with a special fascination for the harpsichord). BIBA: Who are some of the most important musical mentors in your life? QM: One early mentor of mine was my elementary school music teacher, Raquel Lindemann. She was one of the first to see my curiosity for music and provide resources to contribute to my development as a musician. She gave me my first piano lessons, introduced me to some of the first orchestral repertoire I had ever seen (Scheherazade and Bartok’s Concerto for Orchestra), and also encouraged my early attempts at composition. Because of her efforts, I probably wouldn’t be where I am today without her encouragement. Nowadays, I like to seek advice from a fellow composer-conductor whose name is Will White. Mr. White directs his own orchestra in Seattle and is also a prolific composer. Since we share similar interests, his advice and mentorship are extremely valuable, especially since I can relate to it on a deep level. Perhaps the most important mentors in my life since the beginning are a couple, Rogene Russell and Doug Howard. Ms. Russell is a professional oboist and Mr. Howard is a professional percussionist. I met Rogene first at a career day during a presentation she gave about her instrument. She remembers a precocious young man who (to her surprise) recognized every orchestral excerpt she played, even the lesser known ones. The fact that I was around 10 years old at this time surprised her even more. With both of them being orchestral musicians, I then started attending even more DSO rehearsals and concerts. Seeing the orchestra work from the inside-out enhanced my interest in writing for the orchestra and piqued my interest in conducting. Their combined industry experience and parent-like guidance have contributed to my rounding as a musician today and gave me the tools I need to survive breaking into the industry. BIBA: What piece in your repertoire do you cherish the most and why? QM: There is one work of mine that I feel represents me and my current style, and that is a Symphony in B Minor I composed in 2016, called ‘Introspective’. I wrote it while in a deeply pensive mood and as a result, some of my most personal music is contained in this score. The movements have titles like ‘The Forgotten’ and ‘Beautiful Last Days’. I experimented with the harmony and orchestration, and got a piece that had a taste of nostalgia in it. I refer to it as a ‘personal document’ and I still utilize some of the compositional techniques I experimented with in this symphony. With regards to music that I’ve been studying, the one piece that has stuck with me is Stravinsky’s Rite of Spring. I first looked at it during some of my earliest composition lessons, and of course, I didn’t fully understand what I was listening to at the time. As I listened more to it, it grew on me and I came to love every bar of it. It was the rhythms that got me, and to this very day it’s still beyond me how one dude created all of this…in 1913. BIBA: What are some of your upcoming projects? QM: As of the time of writing this (January 2019), I am preparing for several world premieres including: the world premieres of String Quartets no. 2 and 6, a performance of my orchestral work ‘Passages of Joy’ with the South Bend Symphony Orchestra, the premiere of a piece for tuba and string quartet, a new song cycle based on poems of Christina Rossetti, a newly commissioned orchestral work for the Dallas Symphony Orchestra, and some pieces I wrote for friends at SMU, including ‘Double/Bass’ (for two double basses!) and ‘Weapon Wheel’ for three bass drums which I’ll perform with the dedicatees. I’m also doing preliminary planning for my 4th symphony for wind ensemble, to be premiered next year. BIBA: I give you the commission of lifetime! What piece would you compose? What musical forces, duration, performance location/space, etc … ? QM: I’ve always thought that the Bible would make for a really cool epic opera. Imagine it: elaborate and huge sets, expensive special effects for desert and flood scenes and the blending of different styles including oratorio and cantata. It would be a film, but with singing. All of this would utilize an orchestra that would even make Mahler go, “That’s too much, man.” – 6 or 7 woodwinds in each section, like 12 horns, 10 trumpets, 7 trombones, 5 tubas, an infinite percussion section, 6 harps, 5 choruses and a string section of about 100 to match. Of course, this opera would be about 5 hours long, and would probably rotate personnel frequently due to the demands. Where would this be staged? Probably in an open space outside (like a stadium) that could fit all this. Of course, a project like this would never be done during my lifetime, so not too much deep planning is needed! ------- To learn more about Quinn Mason, visit his website HERE, follow him on SoundCloud HERE, and subscribe to his YouTube channel HERE!

0 Comments

On this Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Day, let us reflect upon the dream that Dr. King so articulately expressed for the world - how can the world of Classical music, then, judge composers, conductors, musicians, and musicologists not by the color of their skin, but by the content of their product? If ever there was a musician with such a profound depth and breadth of knowledge and craft, you will find this in Kevin Scott, whose thoughts, interests, compositions, interpretations, and writings never cease to inspire, challenge, and communicate. BIBA: How would you describe your compositional aesthetic?

KS: Not as tough as one would make it out to be. I feel that my music should convey a lack of time. It should not be dated but forever new. Just what new should be defined as is something that its creator should muse about. It can be derivative of old models yet have something new to say from those models, or it can be wholly original with no models whatsoever but have nothing to say. I feel that I embrace both the past and the present: the past through my use of form and structure, the present by using many different styles as long as they don't sound like a mishmash with no purpose. Many composers have embraced a polystylistic mode and I guess I'm one of them if one wishes to analyze what I have composed, but I feel that using a diverse set of tools is simply an arsenal one must have at their disposal in order to create something that is new, different, exciting and certainly invigorating to the mind and the soul. Music should have a significant range, and I try to run that gamut from high drama to zany comedy, although the latter is very, very hard to do unless you have a natural flair for it. I also feel that when I do try to write something with humor it has to still have a structural integrity within the scope of a composition. Prokofiev was accused by one critic of writing individual symphonic movements in his symphonies instead of a symphony where its movements derive from each other. I have tried to write several symphonies, and so far I have yet to find that certain magic that brings those movements together so that they have a continuity and not some sort of random wandering, which I did as a teenager when I first started composing. I just wrote a whole bunch of notes without rhyme or reason, and once you find the right teachers they can guide you to make you find yourself. Some composers have structures so tight that the work sounds feigned rather than organic, and some have no structure whatsoever, yet its melodic content keeps the entire work from sinking to the bottom of the sea. It wasn't easy writing music where you find yourself, and in many ways as you continue to write you do find yourself. You find certain chords that define who you are, you find certain harmonic progressions that you come back to time and again because people will say “ahhh, now we know who this composer is”, because in many ways that harmonic progression is your footprint. And then there's the melodic aspect. My wife says I come up with good melodies though I don't consider melody my biggest strength. Sometimes I drown it out with a tad too much counterpoint! But when you do come up with a strong melodic line it has to move, it has to sweep the audience off their feet and when I do find that line, I make sure it sings on its own and is not encumbered by too much counterpoint! BIBA: Who are some of the composers that you admire for their practice and/or artistic and life philosophies? KS: First of all, the composers I admire the most are those who have remained true to their own aesthetic and have produced music that is both honest to the public and performer as well as works that have a timeless and lasting effect. My list is long, but I've always held George Gershwin close to my heart because he was one of America's first composers that made a major impact on others by his synthesis of jazz, Yiddish theatre and the American popular song of his day alongside a yearning to experiment with many other styles ranging from the impressionism of Debussy and Ravel to the modernism of Schoenberg and his pupil Alban Berg. Berg is also one of my favorites because he himself used much of Schoenberg's compositional methods alongside his love of the great Austro-German tradition ranging from Bach through Haydn and Mozart through Beethoven and Schubert to Mahler, and his music continues to have that timeless element. I love his use of juxtaposing tonal elements, both fixed and ambiguous, while at the same time allowing his music to sing. That we lost both Berg and Gershwin at the zenith of their powers leaves us with a “what if...?” situation where we can only guess which way their musics were heading had they lived to see the impact of the Second World War and its aftermath. This also leads to Mahler, who is after Gershwin my second favorite. I found his music both terrific and terrifying as a teenager, music that grabs you by the throat and shakes you to the core, music that makes you think of the many things he said and would have continued to say had he lived to see the impact of the First World War and its aftermath. His sixth symphony has been deemed prophetic by many, and his incomplete tenth symphony, whether realized in performing editions ranging from Deryck Cooke's bare-bones presentation to Luis Carvahlo's “re-invention”, shows us a new direction in both tonality and a structural sphere where he's already showing us new polyrhythmic elements predating Stravinsky's Le Sacre, but also a transparency in hearing every voice as if they're individual, yet working in sympathetic conjunction with one another. These two symphonies, alongside his second (“Resurrection”) remain my personal favorites. And this leads to other composers close to my own compositional beliefs: Carl Nielsen for his humor and power, sometimes working against each other, and at times also working in alternate worlds where one can feel his tug of war for both the past and his current present to make way for a better future in music; Rachmaninoff for his love of a world no longer his to enjoy except through memories of once was, yet towards the end seeking to incorporate new ideas and not go gentle into that good night; Ravel for his mastery of orchestral colors and elegant beauty; Vaughan Williams for his majesty and epic storytelling through folksong rubbing alongside new harmonic progressions that makes one's emotional body sing with the music; Anton Bruckner also for his humbleness, but also one who sought to experiment by hearing the music of his masters Beethoven and Schubert and synthesizing it with his love of Richard Wagner's dramatic vision, leaving us with an original voice where your soul is either rejuvenated or reviled. And then there's Bernard Herrmann, whom I consider one of America's most neglected figures, both as composer and conductor. Here is a man who didn't suffer fools gladly and told it like it was, even if it meant alienating the closest of allies. His music is straightforward yet never sentimental unless he wants it to be, curt and to the point without adding any unnecessary baggage, colorful not for its own sake but to weigh and mirror every chord, every progression, every nuance of its material to make one think. His scores for the cinema make you think big time about not only what you see on-screen, but also what each character is all about, as if they're right there in your personal presence and not some simple celluloid image. And where, does one ask, are the African-American composers who have played a role in my music and life? Many. William Grant Still is our padrone, for lack of a better term, a man who showed us that we can aspire to our dreams and not allow racism or any other kind of “ism” to disrupt our train of thought in what we want to say and how to say it. And then there's Ulysses Kay, whom I had the pleasure of studying with and performing and recording several of his pieces. Kay was a visionary master whose compositional structure has no holes or weaknesses and also one who stretched the boundaries of tonality, both melodic and harmonic, into a new, albeit subtle, direction. Noel DaCosta, Hale Smith and Ed Bland were mentors who continued to keep me on the “straight and narrow”, always making sure that my music didn't add anything extraneous, stayed true to what you intended to say and not once look at fads merely because they're there to be used. If you found it as a useful compositional tool to add to your arsenal and you had something pertinent to say with it, then by all means incorporate it into your own voice, and this is my key point as to who I am – a composer who is at the crossroads of music, listening to many styles but picking and choosing what's right for what I have to say in my compositions. BIBA: What have been some of your most exciting projects and collaborations as a composer, conductor, thinker, etc...? KS: As a composer? Quite a difficult question regarding collaborations, as I have had very few over the years, but when I wanted to write music for the cinema back when I was in college I had the pleasure of working with two wonderful guys in Bob Zimmerman and Octavio Molina. Both gave me the chance to score their independent films, and one accomplishment I am proud of is scoring Octavio's film “The Avatar and the Neophyte”, which was made in 1977. This is a film that probes the mind of two people who are so different from each other, yet play off against each other, then come to terms with each other and then when the mask is taken off by one of them, reveals the other to be someone that, in their eyes, simply is not who they're supposed to be. Scoring this film was not easy, suffice it to say, as I wanted to incorporate a lot of styles: folk music, free jazz, atonality, modality and even – and this was a stretch for me – avant-garde rock! I would still like to try and hear what I envisioned for the film's original title, as I used electric guitars, rock drummer and a Hammond organ! Maybe one of these days I'll get around to recording the entire soundtrack anew and see what can be done. And then there's my collaboration with R. Jeffrey Cohen who founded the now-defunct RAPP Arts Center, which was located down on the Lower East Side of Manhattan. I inquired to their company via an ad in Back Stage asking if they wanted a composer to write an underscore for their theatrical production of “Ben-Hur”, and this was back in 1989. Cohen had already sought out Philip Glass to score his production of Thomas M. Disch's adaptation of General Lew Wallace's novel, and then when he wasn't available asked Michael Gordon to score it. I believe he turned it down because he also was not available, but I was. I envisioned writing a work for winds, piano and percussion, but Jeff wanted a cello – a lone cello – for some scenes. It worked, and the portion of my score, which was heard in the presentations done in Baltimore, moved Jeff so much he asked me to expand my score for the New York run – for two cellos! This production brought out the best in me as a composer. I decided to use a lot of minimalist techniques, as well as incorporating Judeo-Arabic scales where quarter-tones are not only prevalent, but add a sense of ethereal, almost translucent, beauty to the music. But I also didn't want to see this music forgotten and stay hidden away in a cabinet, so I decided to try and arrange a suite from the score. After musing about what to score it for, I decided to do it for string orchestra, as I felt I could pull more colors out, and at the same time expand the material that would lend itself to a concert format. The first movement, which was the recipient of the Unisys African-American Composers' Forum award by the Detroit Symphony, has been played several times and led to further commissions from orchestras and chamber groups. Over two decades later I met Kirk Smith by way of Yahoo's Orchestralist, and it was Kirk, a conductor based in Houston, who asked me about the suite once he saw the first movement, only to find out that it was more of a jigsaw puzzle than an established work, and it was through his encouragement that I finally finished the suite, which is indeed one of my finest accomplishments in concert music. And then there's my collaborations with conductors such as JoAnn Falletta, Tania León, André Raphel, Leslie Dunner, Yoel Levi and Anthony Aibel, all of whom have performed my music with great aplomb. As a conductor? Even more interesting. I would say that my impact as a conductor of wind band music has had more of an impact than being one for either orchestra or chorus. It was thanks to Mark Strunsky at SUNY Orange Community College who was taken by my credentials and hired me to rejuvenate their college-community band program, which had fallen by the wayside. I had one year to rebuild the group, and what started out as sixteen players at my first concert in April of 2006 became a solidified group of fifty a year later, playing top-notch collegiate repertoire. And it was during this time that I found composers for wind band that would excite me as a conductor and I would go out of my way to promote their music, much to the consternation of some of the players who wanted more of the traditional community wind band fare like Sousa marches or arrangements of familiar Broadway showtunes or Hollywood movie scores. Yet I persevered, and by the time I left the college in the spring of 2014 I had presented eight or nine world premieres, seven New York state premieres and seven local (i.e., Orange County) premieres of works by Dana Paul Perna, David Avshalomov, Gary Powell Nash, James Wilding, Brooke Pierson, Craig Morris, O'Neal Douglas, Kathryn Salfelder, Persis Vehar, Nancy Bloomer Deussen, Ayatey Shabazz and Carlton L. Winston. It was Carlton's music that really captured the imagination of both our players and the audience when I premiered his work “When the Great Owl Sings”, where he was so grateful that he wrote a work especially for us, and we had the chance to premiere “Dionysian Mysteries”, which is one of the most exciting works for wind band to come in a long time. I had hoped that my performance would lead to others, but it hasn't as of yet. The same with O'Neal's “Harriet”, which is one of the most moving works for wind band and deserves – nay, demands to be played by more groups seeking new works that both entertain and enlighten audiences and players alike. But this is not to say that I didn't do this exclusively in the concert band world. I also did my share of premieres with orchestras, such as offering the first European performance of Leo Edwards' Fantasy Overture in Varna, Bulgaria, or the world premieres of works by Craig Morris, Raymond Rosario and Arnold Bieber. And not to stay exclusively with contemporary music, I also offered the first performances in this country, albeit reading sessions, of Norbert Burgmüller's first symphony and Johann Rufinatscha's fourth symphony with the Orchestra Society of Philadelphia. Burgmüller was a friend of Schumann's and died tragically young at 26 before he could really make an impact on German music, and Rufinatscha was a close friend of Brahms who decided not to compose at the peak of his creativity. I should note that Brahms' first two symphonies are, in part, influenced by Burgmüller, while the first movement of Rufinatscha's fourth one hears Schubert and Mendelssohn, yet also Bruckner at his mature moments, and this work was composed in 1849 at a time when Schubert's music was still all but unknown to the world, and Bruckner had yet to compose his F minor “Study” Symphony. BIBA: Where do you see the world of Classical Music in 5 - 10 years? KS: Right now we're in a very strange point in time where one has to define what is 21st century music. We have many different avenues where you have composers who still yearn to experiment and bring diversity to music ranging from the modernist techniques of the latter part of the last century to pop influences of the current one. There are composers out there who simply refuse to compromise their vision of what new music is all about to appease those who feel that new music has lost its way on audiences, and the audiences continue to protest vehemently over being alienated. On the other hand we are witnessing more and more younger composers who are not only embracing tonality, but some of them want to go back to the “old school” of traditional form and content that will make those same audiences who are repelled by the modernist wing embrace this “new tonality”, or “new romanticism” or whatever you want to call it. On the one hand many audiences have fawned over Alma Deutscher, who wants to bring “beauty” back to music in a world where ugliness, in her view, reigns, not only in our current events but even in artistry where it reflects that aspect of our lives. And then you have composers like Quinn Mason and Avrohom Leichtling who absorb all styles of music and yet their symphonies have a rock-solid structure that hearkens back to the great symphonies not only of the “Great American Symphony” tradition from the past century, but also to the post-romantic canvasses we hear in Bruckner, Mahler, Elgar, Schmidt, Hadley, Stanford, Tournemire, Kaun and even early Ives. And yet you have new composers who are attuned to the times, such as Gary Powell Nash, Jennifer Higdon, Christopher Theofanidis, Dan Forrest, Jessie Montgomery, Courtney Bryan, Max Grafe and many others who exhibit a balance of different styles that continue to bring audiences to their feet, and players who are in awe of their compositional prowess. BIBA: I give you the commission of a lifetime and it is without restrictions. What piece would you create? What forces? Duration? etc ... ? KS: Well I certainly would not write a work as big as Mahler's Eighth, Havergal Brian's magnificent Gothic Symphony or the daunting Jama Symphony by Kaikhosru Shapurji Sorabji, tempting as that might be! But if I did have that kind of commission, it would have to be something where I could say “you can't let this money dictate your artistry to the point where you write yourself into frustration.” That said, I would love to fulfill my dream and write my operatic version of Shakespeare's “King Lear”. I know others have done it before, but this play has always been close to my heart since my high school days, and I would love to sit down, tackle the prose and re-structure it without sacrificing Shakespeare's vision, either by myself or with someone I know who would make sure that the Bard is not defiled by any means, and then set that libretto to music. I don't know if I'll get that chance – one has to live long enough to write the magnum opus that is the summation of their creative powers, much like Verdi when he composed Otello and Falstaff which, incidentally, come from Shakespeare! ----- To learn more about Kevin, please follow him on SoundCloud, and follow him on Twitter! by Ashleigh Gordon For Castle of our Skins, January and February are usually busy times of year. While we program year round, we often get asked to program around holidays or anniversaries specific to Black holidays and/or culture. With so many arts organizations and schools looking to fill their Black history month and MLK day celebrations with activities, it only makes sense to give us a call. Right? Well…yes and no.

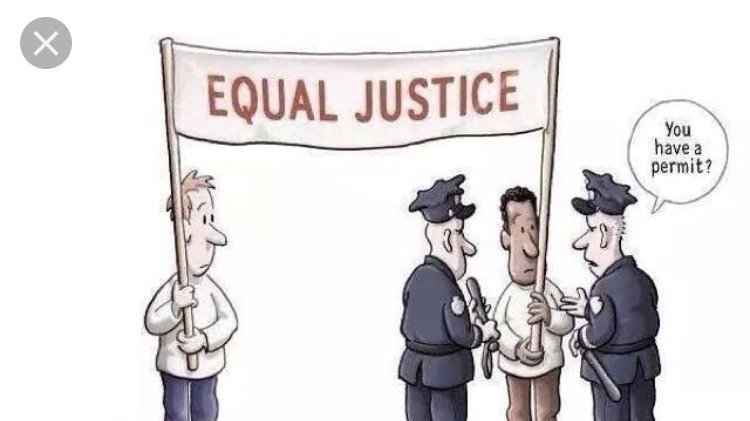

We of course welcome the opportunity to honor Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. on his birthday (Jan. 15, 1929) or the federal holiday that falls on the third Monday each January (the 21st this year). We of course welcome a chance to commemorate the self-appointed birthday of Frederick Douglass (February 14) who, along with Abraham Lincoln (born February 12), were the inspiration behind the 1926 National Negro Week: a week-long tribute which later grew to become the Black History Month celebration we now know. And, being a concert series, we are well aware of National African-American Music Appreciation Month, defined in 2009 by President Barack Obama and held annually during the month of June. (This June, we are excited to celebrate with our “I Am A Man” residency at Hibernian Hall). History and the people who shape it should be integrated into daily life. Powerful moments in time should be remembered throughout the year. Powerful people and their inspirational teachings and actions should be reflected through our own thoughts and doings. Why relegate tributes to single events, anniversaries or public holidays when it becomes a lost opportunity to keep memory and history alive if not done more frequently? I love big celebrations as much as anyone else, but I also find genuine value in small, daily remembrances and reflections. So, as a 2019 resolution, I want to challenge our BIBA Blog readers to celebrate culture, history, and the invaluable teachings both have to offer throughout the year. You don’t need a special opportunity to commemorate an achievement, make reference to something politically current or historical, or pay homage to trailblazers. Likewise, you don’t need a special occasion to simply celebrate artistry for the sake of artistry, and program beautiful music by composers of color. Every day is appropriate. Every day is a time for celebration. by Anthony R. Green The past three to four years (a bit after the foundation of Castle of our Skins) has seen a dramatic rise in conversations about women in Classical music, people of color, non-Europeans, mis-representation and under-representation, programming, tokenism, and other injustices. But the older generation of composers and musicians of color remind me osmotically that these conversations are not new. Just like mass migrations of Black populations in the US from north to south or vice versa, conversations about the injustice in Classical music also occur in waves. What do these waves have in common though? After the conversations ... ... the injustice remains.

Why is this? Is this a fault of the system? Is this a fault in the nature of the conversation? Is this because of laziness or being distracted by other things? I would posit that it is a bit of all of the above. Systemic exculsion is so ingrained into everything that Classical musicians do that we just live with it, refusing to change, acknowledge that we should change, or research how to change. Conversations are so often about the problem and hardly EVER about the solution (as I mentioned in an article I wrote for NewMusicBox last fall). And changing itself requires uncomfortable truths, breaking down comfort zones, and gritty, messy processes; it is easy to start to change, get frustrated, and give up ... or start to change, then get distracted by life, other opportunities, etc ... Not that this blog post can solve everything in one post, but I want to posit that starting to change should begin with modifying our conversation. This can be as simple as throwing in from time to time the term "composers who happen to be ... " (Black, women, homosexual, non-binary, transgender, indigenous, Native American, etc ... ). It is good to remind readers from time to time that the word "composer" applies to all people, like the word "nurse" or "secretary". Including solutions in conversation is another positive step, and a welcome step as I experienced first hand. People want to know what they can do to help, and many will put in the work, and share the information with their network. Lastly, as much as you talk about injustice related to marginalized people, talk just as much or MORE about their achievements in a celebratory way. I cannot imagine Florence Price or William Grant Still wanting to be posthumously remembered primarily for the injustices they endured. It is a new year, and celebrations are in order! Are you with me? |

Details

Writings, musings, photos, links, and videos about Black Artistry of ALL varieties!

Feel free to drop a comment or suggestion for posts! Archives

May 2024

|

Member Login

Black concert series and educational programs in Boston and beyond

RSS Feed

RSS Feed