|

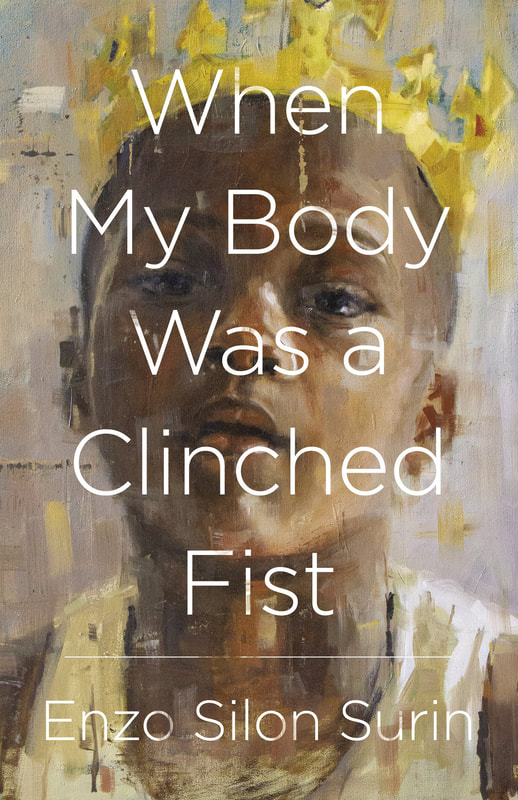

by Ashe Gordon Happy Sunday, COOS and BIBA Fans! Today's BIBA Blog features the Haitian-born poet, educator, publisher, and social advocate, Enzo Silon Surin! He is the author of When My Body Was A Clinched Fist (Black Lawrence Press, July 2020), and the chapbooks, A Letter of Resignation: An American Libretto (2017) and Higher Ground (2006). He is a PEN (Poets, Playwrights, Editors, Essayists, Novelists) New England Celebrated New Voice in Poetry, and the recipient of a Brother Thomas Fellowship from The Boston Foundation and a 2020 Denis Diderot Grant as an Artist-in-Residence at Chateau d’Orquevaux in France. Surin’s work gives voice to experiences that take place in what he calls “broken spaces,” and his poems have been featured in numerous publications and exhibits. Explore more in his interview below! photo by Richard Howard BIBA : You were born in Haiti and lived in New York among other places. How did/do those two worlds shape you and your creative practice as a poet? ESS : The introduction to OutKast’s sophomore album ATLiens is a track titled “You May Die.” The album signified not just a new era in hip hop but in my life as well. I spent most of my childhood being alienated from self, from homeland, in a place that was supposed to be a refuge. As a Haitian-born poet, I immigrated to the United States at a young age, fleeing a country littered with political violence and landing on the shores of another country with just as much social violence. I spent most of my days in Jamaica, Queens, thinking any day was going to be the day that I would die. You can charge that to being a refugee, to New York City streets or to the police that patrolled them. The only safe place was the retreat of my own mind and body. Which eventually led to the discovery of the page as a safe place to frame and tell stories about my experiences. I started to write poetry as a way of expressing my emotions and as a way of getting through the day. It was a matter of survival, really. Being a product of two countries, I drew from my Caribbean roots and our penchant for telling stories and mixed that with the rhythm and cadence of my new country’s burgeoning hip hop culture. And since English was my third and not my first language, I fell in love with the process of trying to find the right combination of words to be able to tell an effective and compelling story. To this day, I consider the dictionary and thesaurus to be a poet’s best friend, and the page is still a very safe place for me. BIBA : You describe your work as amplifying experiences that take place in “broken spaces”. What do you mean by this and can you give an example of a "broken space"? ESS : When I write about broken spaces, which is a term borrowed from Afaa Michael Weaver’s poem “Blues in Five/Four, the Violence in Chicago”, I mean the places that most of us would rather forget. I am referring to the crevices that Black and brown folks often fall into, the cracks of society, the wrinkles & folds, the corners and other spaces we call home, only to be traumatized within them or forced to live out past traumas. These spaces are also often forgotten places that have collapsed over time, which means that some of the people who inhabit those places are also out of sight and out of mind. In other words, no one is really checking for them under the rubble. Yet, within these same spaces, people make a living, make a way out of no way, make the best of each day by writing or rewriting the narrative of their demise. These are the experiences that are amplified in my work and also in the work of the writers I publish through Central Square Press. An example of a broken place would the title poem for my forthcoming book, WHEN MY BODY WAS A CLINCHED FIST, which chronicled the years my mind and body endured while growing up in Queens, NY from the mid-eighties to the mid-nineties. When I was 13, I witnessed someone being beaten within an inch of their life over a glare. As a youth, I also witnessed odd exchanges between rival posses: sanctioned peaceful football games and fights scheduled at a specific time and location. The violence wasn’t always chaotic—sometimes, it was a methodical type of violence that was predicated on an odd respect for order—but more often then not, it would erupt like one held the balance of the universe within their fist. On the way to and from school, that’s the world I navigated. It’s the world I try to chronicle through the eyes of a little boy who spent 10 years of his life negotiating this terrain. That is still someone’s reality today and I’ll keep writing about it until we figure out a way to mend these broken spaces together. BIBA : What drew you to create your own publishing company, Central Square Press? ESS : The idea for Central Square Press was born out of numerous heartfelt conversations with my peers about the perilous journey to get their work out into the world. These folks were phenomenal poets, some with MFA degrees and beyond, who had very-little-to-no success finding a home for their book manuscripts. At first, I just wanted to create an opportunity for these poets to publish their work, you know; to provide one more entry point for manuscripts trying to make their way into the world. However, thanks to an organization that released a report with the acceptance rates of journals and publishers based on demographics, I was able to see the dismally low percentage of Black and brown writers being published, especially female writers. We decided to narrow focus and publish underrepresented writers, especially those whose poetry reflects a commitment to social justice regarding African American, Caribbean and Caribbean-American communities. In addition, the number of independent Black publishers is very low compared to what it used to be while hundreds of Black writers come out of writing programs every year. I was very conscious about needing to launch a small press by a Black publisher. The conversation in many circles I frequented rarely went beyond our roles as writers in publishing; it shifted from the lack of publishing opportunities to the creation of publishing opportunities. We often want to be published but not necessarily become those who publish other writers. As a result, we fall in line with a pre-determined path for publication, even when it doesn’t successfully serve us in a way that is always fruitful. That wasn’t always the case and I wanted to draw from the lineage of Black publishers who created opportunities for other Black writers. Cover art: “When I Ruled the World” by Carlos Rancaño

BIBA : As an educator, what are some of the tools you share with your students (or use yourself) to help craft a compelling story? Are they different for poems vs. short stories vs. non-fiction? ESS : I have dedicated my life and career to affecting social change through creative and critical writing. As such, it is important that my students are exposed to all the necessary tools available in the writer’s toolbox. Whether they are writing poetry, fiction or non-fiction, I always challenge my students to remember their goal—the point of writing the story—and whether their goal to write a compelling story has the reader in mind. One tool I often focus on in my creative writing workshops is something called the human scale. It is a term that I borrowed from the field of architecture, which is used the determine whether or not a particular design has considered actual human beings inhabiting the space. I use the term to remind my students that another human being will be reading their work and to always keep that in mind. Literary devices are tools to enhance a story and are not the story themselves. The average reader can tell when a writer is more in love with language than the story they want to tell. As such, my focus during the drafting process is to pose questions for them to entertain more than it is to provide line suggestions or feedback. I want my students to fully interrogate their own work before declaring a story or poem is complete: Have they left enough room for the reader to inhabit the lines of the poem? Have they considered the different ways a reader might enter a story? What hasn’t been said that needs to be said? What do you want the reader to walk away with? What will leave them satisfied or wanting more? With the last question, both elements are essential to writing a compelling story or poem. As a writer, one should always want a reader to feel full or wanting more but never satiated or famished. BIBA : Your new, full-length debut When My Body Was A Clinched Fist is a coming of age story "where hip hop and Haiti flow through the borough of Queens" (Tara Betts, author of Break the Habit). Can you share the process of working on this work, reliving moments from your childhood, and how that affected you as an adult today? ESS : The decision to write When My Body Was A Clinched Fist was not a complicated one, but it certainly was one of the toughest things I have done in my life. At some point, I realized the anxiety from which I suffered most of my adult life was connected to the pathology of fear I experienced as a youth. The collection was written as a way of coming to terms with what was a very difficult decade of my childhood in Queens, New York, one that would follow me well into adulthood. I wanted to chronicle the experience of growing up in an environment prone to social violence, where a simple walk down the street could lead to serious, and at times, deadly predicaments. However, I also wanted to address the human element in such circumstances and the versions of ourselves that are created when faced with these predicaments, and the sometimes detrimental effects of choosing not to participate in the violence. In a poem titled “My Body As A Clinched Fist”, I tell the story of what it felt like to watch a schoolmate get beat up by a mob simply because he looked at someone the wrong way. The incident happened when I was 13 years old and it had taken me almost three decades to be able to write about it. Such experiences were always readily available to write about, but in writing about them I would have to relive each moment. That type of emotionally challenging and creative work is necessary for a breakthrough, but it takes times—it took over ten years for the collection to come together. I am a freer and healthier person because of this book, and I hope it will help others to be a bit more free in their own lives.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Details

Writings, musings, photos, links, and videos about Black Artistry of ALL varieties!

Feel free to drop a comment or suggestion for posts! Archives

May 2024

|

Member Login

Black concert series and educational programs in Boston and beyond

RSS Feed

RSS Feed